In 2003, the African Union (AU), in a formal declaration, recognised the African diaspora as its “sixth region.” The AU Constitutive Act, in Article 3(q), encourages the full participation of the diaspora and underscores their significance in capital investment, transfer of expertise, cultural exchange, and political advocacy. Lamentably, similar to other areas in the Global South, barely any concrete steps or frameworks have been sustained for the inclusion of the diaspora, despite the enormity of the group’s potential.

The emphasis placed on ‘sustenance’ is deliberate. In February 2025, at the 38th Ordinary Session of the African Union, a Diaspora Legal Framework was finally endorsed more than two decades after the initial declaration. While the framework outlines the criteria and procedures for Africa’s diaspora’s engagement with the Union, it is perhaps too early to measure the viability of this framework in coalescing the untapped potential of the African diaspora.

Background

Migration, a historical concept, stems from a complex interplay of factors, including economic prospects, political volatility, and social aspirations. The tendency towards a ‘recency bias’ regarding the subject of migration is perhaps a legitimate accusation that northern social scientists cannot dismiss. American sociologists have been critiqued as cherry-pickers, with extensive focus on post-1965 migration and an ‘exaggerated newness’ of contemporary migration.

Perhaps it’s no coincidence that the timeline of this ‘exaggerated newness’ commences during the 1960s–70s, a period that marked the political independence, so-called, of 50 Global South states across Africa, Asia (including the Middle East), Latin America, the Caribbean, and Small Island States. In the two decades following independence, 38 of the newly independent states, representing an astonishing 76 per cent, experienced periods of political instability, coups, and civil wars that contributed to increased migration. The outcomes remain evident to this day, although their underlying causes are far more complex.

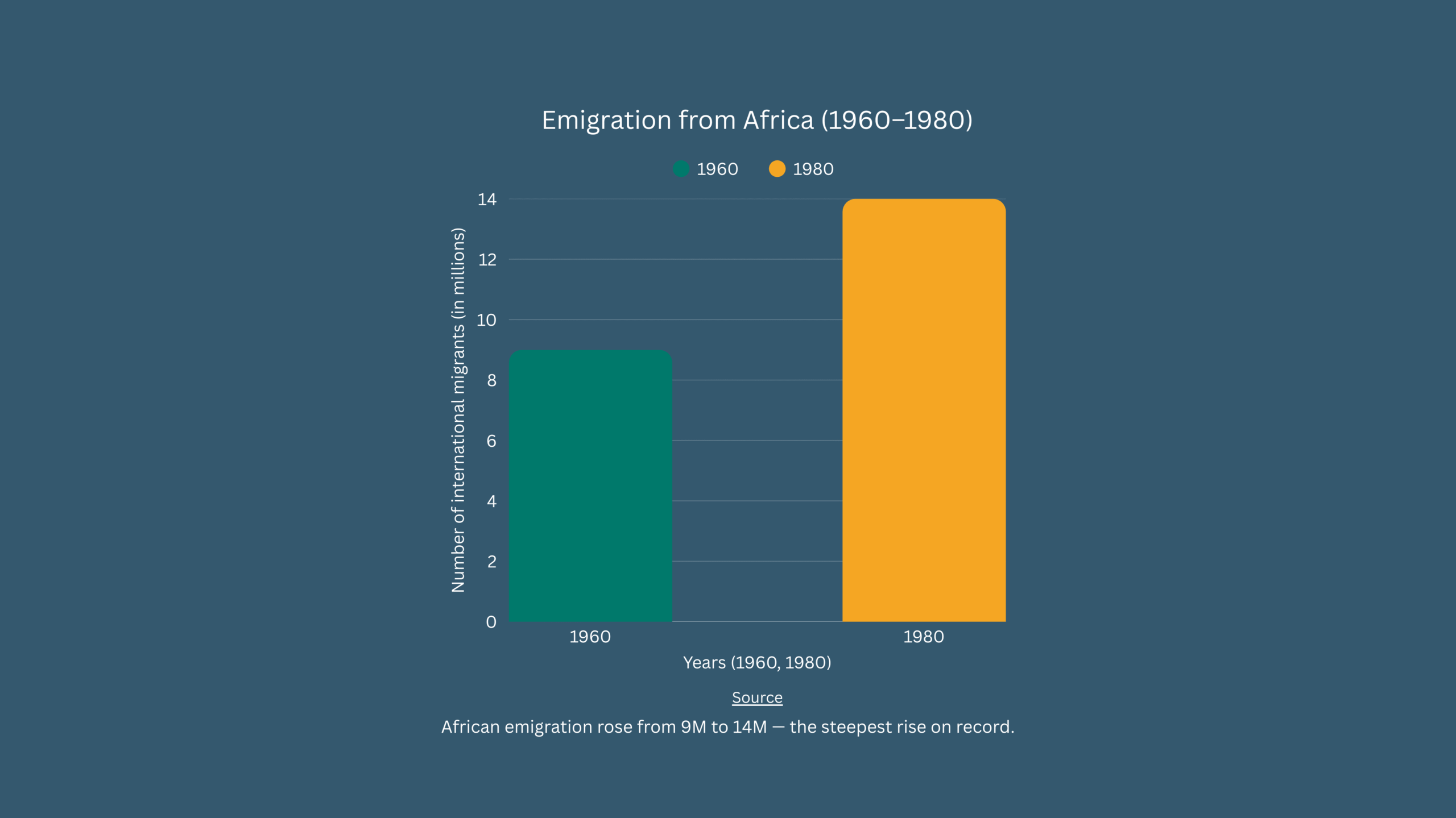

Newly independent post-colonial experiments faced the challenge of navigating the identity crisis of acquired concepts of Western democracies. They had to grapple with the socio-political implications of governing culturally heterogeneous ethnicities within newly formed multi-ethnic Global South states held together by the fickle stroke of a colonial pen. These pressures often erupted into instability and violence, most tragically exemplified by the Rwandan genocide, and, in this context, emigration from Africa saw its biggest increase between 1960 and 1980, with the number of international migrants rising sharply from nine million to 14 million.

The timeline ‘cherry-picking’ by northern sociologists is perhaps not isolated; it appears to have contributed to the mainstream disregard for migration as a human phenomenon, projecting it solely as a Global South issue. This has induced an atmosphere where post-slavery and post-colonial African/Caribbean, Middle Eastern, Asian, and Latin American migrants to the Global North are at the receiving end of harsh right-wing rhetoric, which has increasingly translated into stricter anti-immigration policies.

Far-Right Politics and Anti-Immigration in the Global North

Interestingly, a clear pipeline exists between crisis situations in the South, subsequent emigration, and the mobilisation of diaspora advocacy groups in the Global North. Iraq, South Sudan, Syria, and Palestine are among the many states where diaspora advocacy has intensified following political crises at home. In many of these cases, the complicity of the North, both historic and ongoing, is unmistakable.

The American Immigration Council has described the first six months of President Trump’s second term as the “most significant changes to U.S. immigration policy in the nation’s history.” Trump’s unprecedentedness is not in isolation. Canada, Belgium, Germany, the United Kingdom, Austria, Italy, and the Netherlands have announced tighter migration policies as centrists or ostensible centre-left governments chameleonise to appease the sensibilities of the far right. The United States’ deportation of students involved in pro-Palestine protests and the United Kingdom’s designation of Palestine Action as a terrorist organisation echo the increasing northern intolerance for diasporic advocacy amidst rising far-right pressures.

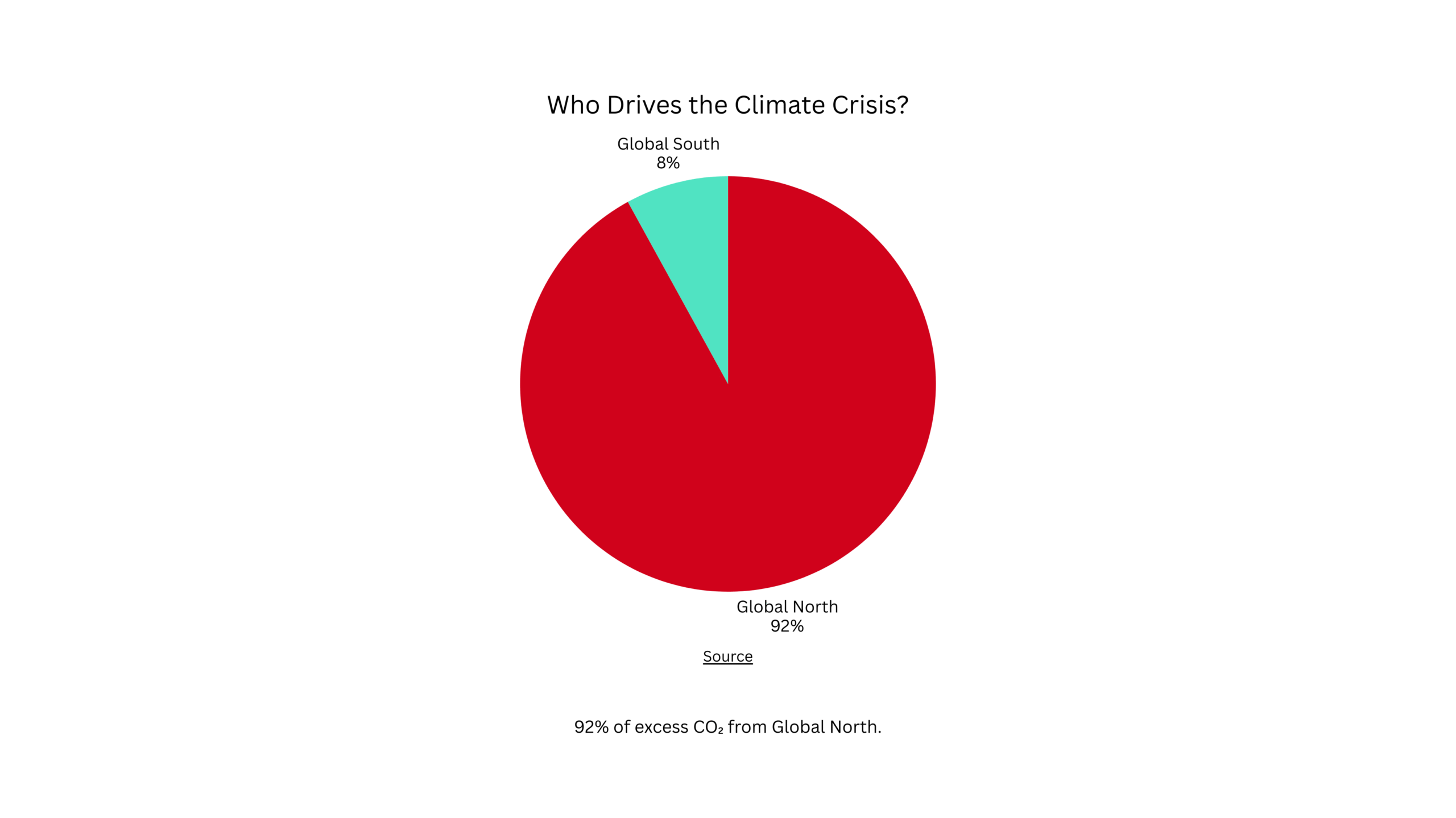

One may argue that the focus of the northern leadership ought to be on acceptance and corrective measures aimed at limiting centuries of political interference, resource extraction, and arms sales that contribute to forced displacement from the Global South. Instead, alarmist rhetoric aimed at undermining the legitimate reasons for cross-continental migration patterns has displaced reasonable dialogue. For instance, there is a tendency to “securitise climate migration” and cast Global South climate refugees as causes of violence and security concerns in the Global North. Paradoxically, it is the Global North that serves as the dominant driver of climate disaster in the South, contributing approximately 92 per cent of excess global CO₂ emissions.

In January 2025, one of President Trump’s executive orders on stricter border policies declared the U.S. Refugee Admissions Program to be detrimental to the United States. The order also suspended the programme, which had been in place since the Vietnam War, a conflict emblematic of extensive American foreign intervention, and which had provided refuge to people fleeing crises in places such as Cambodia, Darfur, Bosnia, and Myanmar. A notable exception was subsequently made to this suspension: white Afrikaner farmers from South Africa.

With the surge in far-right-led anti-immigration policies across Europe, coupled with the Global North’s efforts to suppress diaspora advocacy groups, the question arises: what will be the fate of these movements? Will they be compelled to regroup within their countries of origin, or will they be forced to coexist under conditions of increasing northern impunity?

Challenges and Dynamics of Diaspora Advocacy

Diaspora advocacy is supported by economic resources that are limited in the Global South. This not only underscores the structural barriers impeding the visibility of grassroots causes but also highlights the dependence of Global South human rights initiatives on the North for both sustenance and legitimacy. As the New Internationalist observes, an atmosphere of ‘NGO-ization’ has emerged, in which grassroots groups from Africa, Asia, the Middle East, and Latin America must adopt Northern frameworks and funding models to survive, thereby compromising their autonomy and, in many cases, ‘diluting their radical essence’.

While studies indicate that the human rights record of the North is taking a nosedive, especially in the wake of media censorship, attacks on protest rights, and a weakened rule of law, its economic power highlights how access to resources and prosperity is central to shaping global advocacy. This leaves diaspora advocacy groups with little or no chance of resettling in the South, as the resources and ‘legitimacy’ for their work are tied to the North.

If Not Advocacy, What?

Lamentably, efforts to strengthen the economic sustenance of the Global South, such as the BRICS coalition or bilateral calls for the strengthening of local currencies and reduced dollar dominance, are being met with opposition and threats from the United States. It appears that the current dynamic between the Global North and the Global South, marked by economic extraction and inequitable trade frameworks that delegitimise local production, is preferably ‘addressed’ through the piety of charitable humanitarianism and global advocacy.

Proponents of modernisation theory argue that economic development leads to democratisation and improved human rights standards through structural change. Inglehart and Welzel posit that economic development shapes value systems in ways that foster democratic governance and enhance the protection of human rights. Stephen Hopgood similarly suggests that the economic development of the Global South can strengthen human rights outcomes without reliance on global advocacy mechanisms. In this context, development is a result of inclusive policies and the strengthening of institutions.

While an argument for the substituting global south advocacy with diaspora led development initiatives would be impractical, there exists the need to include spotlight the exigencies of development both theoretically and on the ground. Firstly, the focus of diaspora advocacy groups must shift to mainstreaming the North’s underdevelopment of the South and the need for the latter’s autonomy over its own resources and politics. This serves two significant roles: It highlights the causes as opposed to just the symptoms of Southern problems which previously warranted humanitarian interventions and it focuses diaspora led engagements on economic and policy involvements to counteract the existing underdevelopment of the South.

While an argument for substituting Global South advocacy with diaspora-led development initiatives would be impractical, there remains a need to spotlight the exigencies of development both theoretically and on the ground. Firstly, the focus of diaspora advocacy groups must shift toward addressing the North’s role in the underdevelopment of the South and the imperative for the latter’s autonomy over its own resources and politics. This serves two significant purposes: it highlights the root causes, rather than merely the symptoms, of Southern challenges that previously warranted humanitarian interventions, and it directs diaspora-led engagements toward economic and policy strategies that can systematically counteract the entrenched underdevelopment of the South.

Secondly, although agenda-setting and thematic emphasis on development within diaspora advocacy coalitions may seem feasible, a critical loophole remains. The artificial heterogeneity of African states, cultivated by colonial powers during the Berlin Conference of 1884–1885, means that while post-colonial states hold formal economic and political authority; Identity, influence, and loyalties remain highly ethnicised. This has created an exploitable loophole, whereby ethnic factions can be co-opted and armed to weaken Global South states and secure direct, cheaper access to resources for Northern powers. This political playbook has been repeatedly deployed in several failed states, most notably in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

One may argue that the unification of diaspora groups across different ethnicities could promote greater cohesion in the home country and reduce the likelihood of any single tribal group or ethnicity being co-opted. However, this view may overestimate the influence of diaspora groups over the deep socio-cultural effects of historic allegiances and divisions.

A plethora of Global South ethnic tensions are spilled over and perpetuated by diaspora members in the Global North. For instance, conflicts between Hindu and Muslim groups, as well as between Turkish and Kurdish communities, have been transported into diaspora populations in European cities such as Leicester, Bradford, Paris, and Berlin. This phenomenon is comparable to the reterritorialisation of conflict among Rwandan Hutus and Tutsis, who reinterpret conflict narratives, historical accounts, and genocide commemorations within host countries such as Belgium and Canada.

Conclusion

Diaspora advocacy operates at the intersection of historical legacies, structural inequalities, and ongoing political and economic pressures from the Global North. Despite formal recognitions such as the African Union’s designation of the diaspora as its “sixth region” and the recent Diaspora Legal Framework, the mechanisms to fully harness diaspora potential remain underdeveloped. The North’s role in shaping migration patterns, securitising climate refugees, and enforcing restrictive policies continues to constrain the autonomy and effectiveness of diaspora movements.

At the same time, the Global South’s internal dynamics including ethnic heterogeneity, historical allegiances, and vulnerability to external co-optation limit the extent to which diaspora unification alone can address structural challenges. While coordinated diaspora efforts may promote cohesion and mitigate some external interference, they cannot entirely resolve deep-seated socio-political complexities at home.

Yet, there is strategic potential. By reorienting advocacy toward addressing the North’s role in underdevelopment, supporting local economic and political empowerment, and focusing on root causes rather than symptoms, diaspora movements can contribute meaningfully to structural change. Their engagement must balance international advocacy with bolstering local agency and institution-building to maximize impact.

This synthesis of challenges and possibilities perhaps leaves us with a thought-provoking impasse: is the development of the South ultimately contingent on the unification of Global South diaspora movements, or must new frameworks emerge that integrate diaspora engagement with robust local empowerment? The answer remains uncertain, but the stakes for advocacy, development, and the future of the Global South could not be higher.

Featured image: Credit: Nitish Meena on Unsplash. Infographics by Aarya Dhital, Research Consultant & Specialist on South Asia at Global Divide.