The segmentation of the globe into a ‘North’ and a ‘South’ in policy conversations transcends geography. Although, recently, the status quo is being modified to accommodate broad multilateral interests, an emerging BRICS, and a protectionist America; strictly defined global economic hierarchies from the 19th century have perpetuated a two-tiered socio-political system of Northern dominance and Southern deprivation.

In the international civic space, Northern interests and Southern civil societies interact on the premise of a ‘humanitarian-saviour’ framework which engenders aid-powered donor/recipient relationships between the former and the latter. The resurgence of far-right sympathies across Europe and North America has led to pushbacks and cuts to existing humanitarian funding to the South. The excessive reliance of southern civil society organisations on Northern funding as opposed to ‘developmental-collaborative’ relationships is deserving of its own critique. However, the preservation of these civil societies in the wake of painful donor cuts is timely and imperative for the efficacy of grassroots initiatives and the survival of intersectional minority groups.

What Lies Ahead for Global South NGOs Amid Painful Donor Cuts?

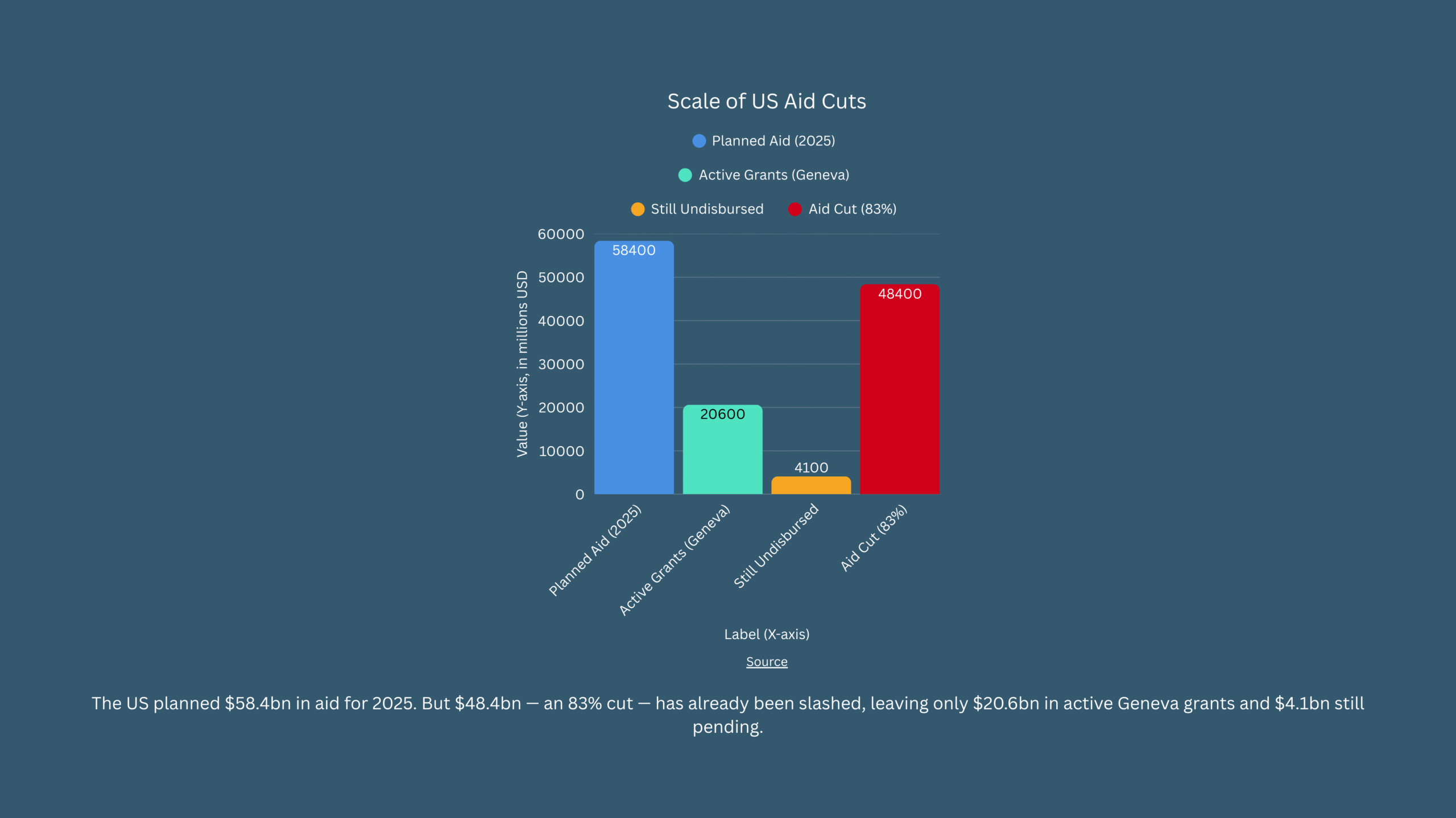

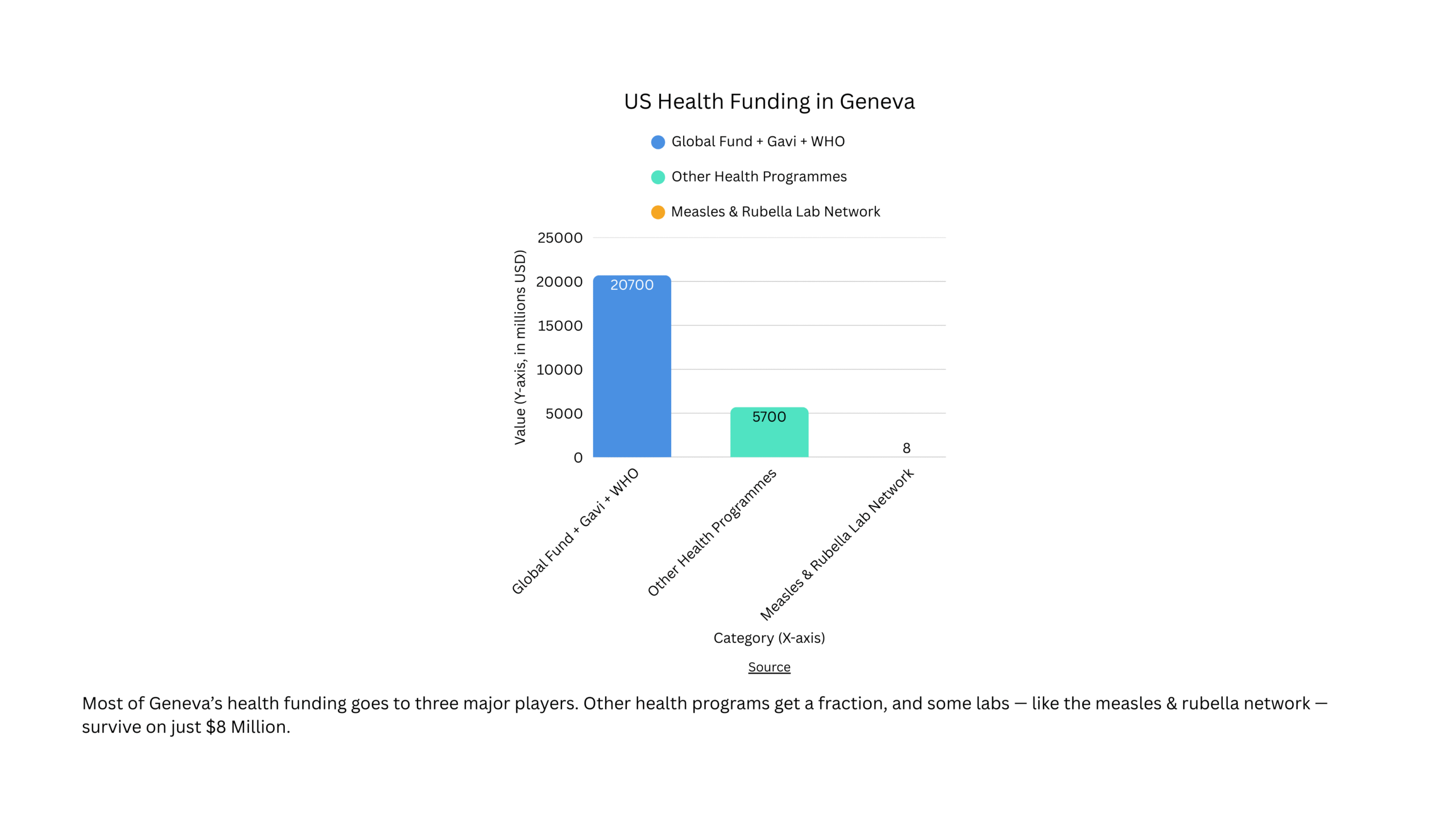

With nearly 300 million people around the world relying on humanitarian aid, budget cuts could result in starvation and, in other cases, the termination of ongoing projects serving vulnerable populations in different parts of the Global South. It is estimated that, in the area of global health, 25 million people could be affected by the funding cuts over the next 15 years.

The political atmosphere in many Northern countries raises fears that newly implemented humanitarian cuts may not be merely seasonal, NGOs may need to strategise for the long haul to preserve the work done on the ground. Asides the United States, Germany, Switzerland, France, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom are among the countries that have either discontinued or reduced aid contributions as part of a “worrying global trend of budget cuts for the humanitarian sector.”

Private Funding

Government funding is often subject to the whims of fiscal and political priorities, which research indicates contributes to its vulnerability. Kate Schecter from World Neighbours recommends a shift from excessive reliance on government funding to focusing on private funding from family and corporate foundations. Although some private funders are not without business or policy considerations, Kate argues that they typically have prolonged commitments to projects beyond yearly or biennial grants. These long-term commitments also entail a holistic and collaborative approach to social projects, which many argue is not characteristic of the foreign humanitarian assistance framework.

A prevalent challenge to private funding is its limited resources compared to foreign government assistance. However, unlike foreign assistance, which often insists on the specific type of project that grants should be allocated to, private funding offers more flexibility, ensuring that multiple private funds can be allocated to one project. The limits of private resources and the inability to sustain decade-long humanitarian aid paradoxically motivate the creation of self-sustaining communities independent of support. Private funders who may not afford the luxury of handing out decade-long grants or assistance like foreign governments prioritise proffering decisive and crucial solutions to local issues.

Additionally, private funding also encompasses the evolution of social enterprises which are self-sustaining business models that offer social benefits while generating revenue. In many cases, these returns are further re-invested into grassroots initiatives creating a cycle of economic and social benefits.

Addressing The ‘Chaperon’ Issue

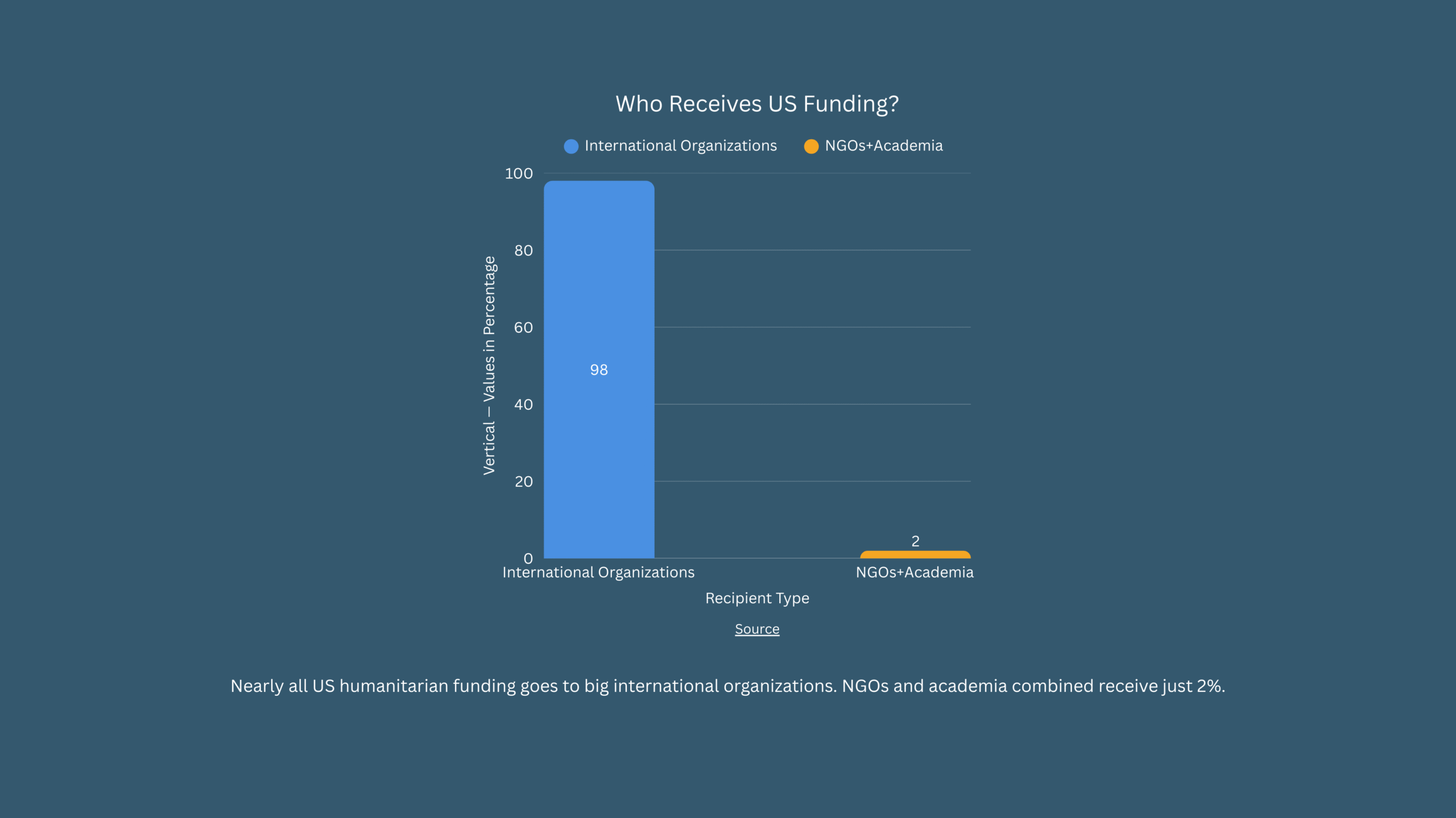

According to The New Humanitarian, the practice of sending government donations through UN agencies and ‘big international organisations’ has created an unsustainable ecosystem where the majority of funding is, in reality, expended on the maintenance of these organisations, with few resources trickling down to the grassroots. The ‘Chaperon’ situation with UN agencies and private contractors has long been institutionalised with the intention to ensure that humanitarian funds are channelled through northern middlemen.

However, statistics reveal that this has resulted in large Northern-based organisations competing for aid, rather than distributing it to Southern civil societies. Astonishingly, 90 per cent of British aid is retained by British firms and international NGOs, with the Global South receiving only 3 per cent. Many large INGOs compete for and retain funds that could have been better deployed on the ground, while publicly cosplaying the cause of local organisations for branding and to bolster their own legitimacy. In the present scarcity climate, increased financial autonomy for local organisations could potentially ameliorate skyrocketing hardships since they possess specialised insights and useful domestic know-how.

Humanitarian Aid versus Development Initiative

While the humanitarian versus development framework is deeply entrenched and systemic, the present funding climate necessitates an accelerated approach to development that ensures reduced dependence of deprived communities on limited aid.

For instance, the IRC, in its work with urban refugees, has recognised the need to devote some of its efforts to removing existing impediments to formal banking for refugees through pushing for policy directives that ensure that financial institutions formally recognise the group as potential clients. This addresses one of the causes of financial dependence of urban refugees as opposed to humanitarian aid which in most cases provide food items and stipends which are not sustainable solutions and lead to increased reliance and dependence on these aids.

A multi-layered approach to development that includes policy advocacy, systemic reforms tailored towards the socio-political causes of dependence and global inequality creates sustainable and long term solutions for communities. Herein lies the dichotomy between ‘handing out a fish’ or sustainably ‘teaching an individual how to fish’.

Rationing the Little

Limited funds presently in the coffers of NGOs can be maximised through cost evidence and data analysis, evaluating both the cost effectiveness and social impact of projects within an NGO’s portfolio. In unusual times such as these, considerations such as politics, funder interests, or visibility should not override the primary motive of efficacy.

In the wake of many Global South NGOs dialing back their international advocacy, the international policy space risks being dominated by those with the most resources rather than those with the most at stake. Indeed, 61% of grassroots NGOs in the Global South report scaling back or shutting down international advocacy due to funding withdrawals (CIVICUS 2023).

Global Divide addresses this gap through policy representation services for Global South NGOs at key hubs of international policymaking. By supporting submissions, oral interventions, diplomatic representation, and ethical lobbying at UN committee hearings, Global Divide’s network of Southern-born policy experts ensures contextual sensitivity and political awareness. Its collaborative model safeguards grassroots narratives, keeping them intact and central to international discourse.

As donor crises, shrinking civic space, and procedural opacity erode access for Global South voices, Global Divide provides the structure, expertise, and solidarity needed to reverse this marginalisation—advancing a decolonised and collaborative approach to global governance.

Conclusion

The era of predictable donor generosity is waning, and with it the illusion that Global South NGOs can indefinitely rely on Northern intermediaries to channel both funds and influence. What lies ahead is not only a test of endurance but an opportunity to reshape the rules of engagement. To survive, NGOs must diversify funding streams, embrace private and social enterprise models, and insist on bypassing the costly “chaperon” system that sidelines them in favour of Northern gatekeepers.

Yet survival alone is not enough. The moment calls for Global South NGOs to claim greater political space in shaping global policy, not as passive recipients of aid but as equal architects of solutions. Global Divide positions itself within this transition: a partner that transforms grassroots expertise into policy influence, ensuring that those with the most at stake set the agenda. In a future of shrinking resources and widening divides, it is precisely the voices from the margins that must move to the centre of global governance.

Featured image: Credit: Masjid Pogung Dalangan on Unsplash. Infographics by Aarya Dhital, Research Consultant & Specialist on South Asia at Global Divide.