The eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) – especially North Kivu province and Goma – faces a “double blow” of armed conflict and climate change that disproportionately burdens women from marginalized and minority communities. In this conflict-prone region, increasingly erratic rainfall, floods and landslides, drought, deforestation and resource extraction have destroyed livelihoods and fueled displacement. Climate shocks amplify pre-existing inequalities: women’s traditional roles (fetching water, firewood, farming) make them especially vulnerable as resources shrink. For example, recent flash floods in Kalehe territory destroyed local markets (where women predominate) and forced women to walk many kilometers in search of water and fuel. Persistent rainstorms since late 2023 have triggered deadly floods in Lake Kivu’s communities (including around Goma), killing hundreds and displacing thousands. These disasters break homes and fields and severely worsen food insecurity (over 26 million Congolese now face acute hunger). With limited infrastructure or warning systems, impoverished and conflict-weary households – especially those headed by women – struggle to cope, highlighting deep climate injustice in Goma’s vulnerable communities.

Gendered Impacts of Climate Hazards

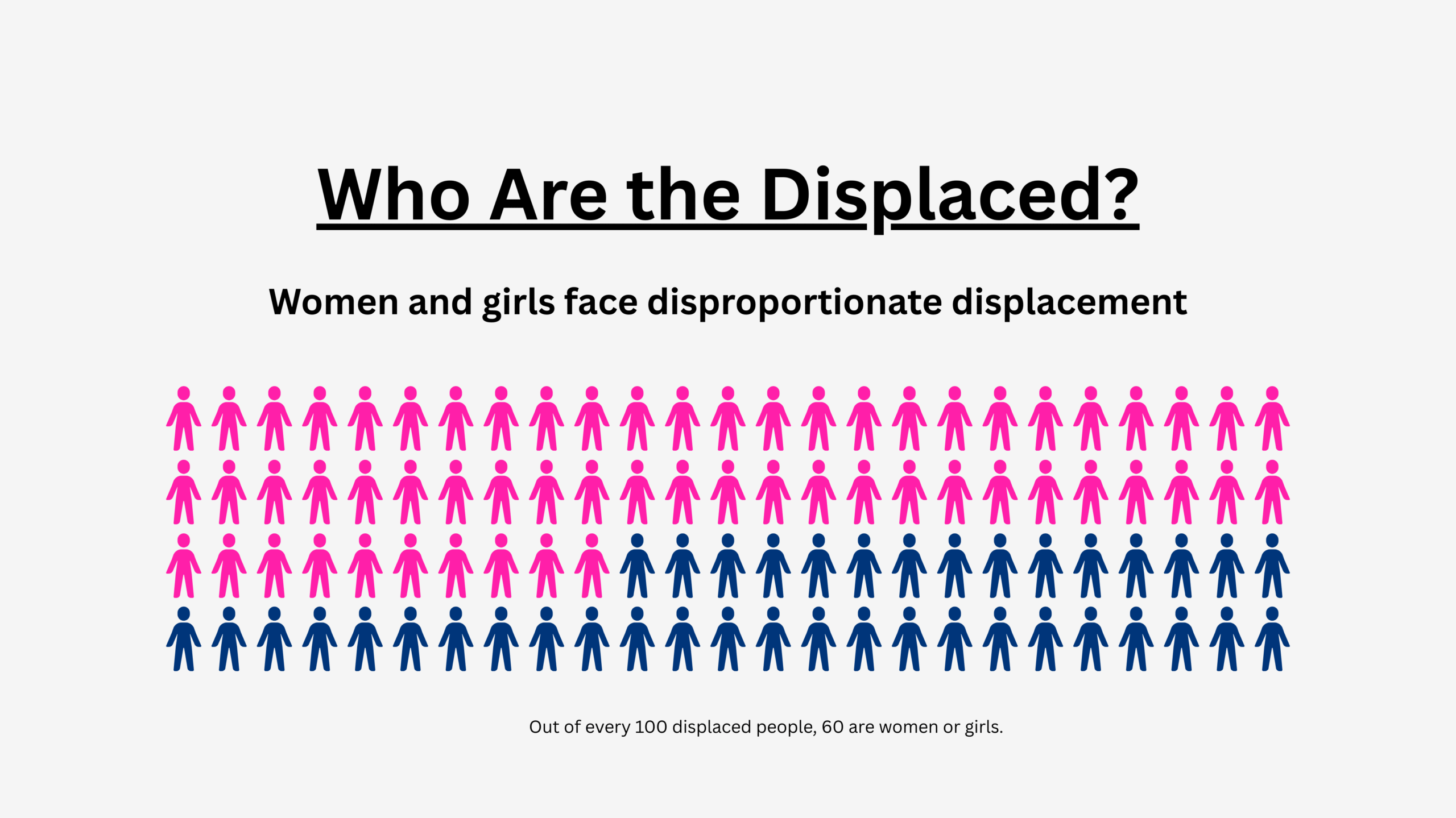

Women in North Kivu carry multiple burdens under climate stress. By cultural norm, men typically prepare fields and own land, while women do the planting, harvesting and domestic chores. When rains fail or landslides hit, households often go hungry. Women – who also collect water, firewood and medicinal plants – must then walk ever longer distances for diminishing resources. In extreme events, displacement and economic collapse disproportionately impact women: in Goma’s 2024 IDP camps, for example, 58–60% of the displaced are women and girls.

Conjunctions of drought and conflict drive “resource grabs” and scarcity: as one analysis observes, “rising livelihood stress…breeds domestic violence,” leaving women at heightened risk. During floods, women and children are often the last to evacuate low-lying areas and suffer most from lack of information and aid. In short, climate shocks – flooding, crop loss or chronic water shortages – compound existing inequalities: women’s workloads increase (growing food, fetching basics) even as their access to land and income remains constrained.

- Floods and landslides: Torrential rains in recent years (e.g. April 2023) have destroyed dozens of homes and roads around Goma and South Kivu, isolating communities and ruining farmland. In South Kivu’s Fizi territory, for instance, thousands were affected and infrastructure wrecked by late-2023 floods. Because women often subsist through small-scale farming or market trade, such disasters erase their livelihoods.

- Food insecurity: Eastern DRC has alarmingly high hunger levels – over 26 million people face crisis or worse food insecurity – and climate variability worsens this. Droughts turn fertile fields to dry savannah, forcing women to spend more time growing or purchasing food and less on education or income.

- Water and energy scarcity: Deforestation (for agriculture, mining or settlements) and erratic rains mean water sources are unreliable. Women must travel further to fetch water or firewood, often through unsafe terrain. This not only increases their labor but also exposes them to exploitation and assault.

Indigenous and Minority Women: Multiplied Marginalization

The DRC’s indigenous minorities – especially the Batwa (“Pygmy”) and Bambuti peoples in North and South Kivu – suffer layered injustices from conflict and environmental change. These groups have been violently dispossessed of ancestral forests by armed actors and conservation authorities. Forests and land provide their housing, culture and livelihood, so climate-driven deforestation and militarized evictions hit them hardest. Reports document that park rangers and militias have attacked Batwa communities in Kahuzi-Biéga and elsewhere, committing atrocities (including murder and mass rape of women) to clear the land. In recent fighting, UN agencies estimate some 237,000 people (many Batwa) were forced from their homes in Kivu.

Indigenous women face acute hardship: customary marginalization means they seldom hold land rights or political voice, even as climate change forces them to spend hours daily fetching scarce resources. A UNDP study found indigenous women in remote DRC must sometimes walk three hours carrying heavy water jugs or wood, often through dangerous forests. These treks expose them to violence and illness; community surveys note women “walk for three hours…crossing swamps and streams…exhausting” under seasonal stress. Meanwhile, they are frequently excluded from meetings or decision-making on land use, missing critical climate information. In sum, the convergence of ethnic discrimination, loss of forest land (from logging/mining), and extreme weather leaves indigenous Batwa women especially destitute and vulnerable. Many now live cut off from livelihoods, lacking medicines from the forest and at risk of starvation and gender-based violence.

Displacement, Gendered Risks and Protection Gaps

North Kivu – and Goma in particular – is now a massive IDP crisis hub. By late 2024, roughly 1–2 million people (primarily from conflict zones) are displaced around Goma. Many fled violence in Ituri and South Kivu, but a significant minority left because of floods or volcanic landslides. Overcrowded camps and unofficial sites encircle the city. Women and girls comprise the majority of this displaced population, straining social safety nets. Humanitarian reports note that food and shelter shortages have led women into survival strategies that endanger them (e.g. transactional sex, child marriage). In camps with little lighting or policing, women collecting firewood or using communal latrines face high sexual violence risk. The Refugees International analysis warns that GBV incidents have “increased five-fold over the last year” amid Goma’s collapse of aid.

Gender-based violence is used as a deliberate tool in eastern DRC’s crises. Armed groups (and even some state actors) have long weaponized rape and abduction, especially targeting displaced women and minority girls. In one testimony, youth escaping militia raids described how girls were abducted into sexual slavery while villages burned. Female IDPs report being coerced into “survival sex” or early marriage in camp contexts. Domestic violence also spikes: as DGAP notes, stress and power shifts under climate-disrupted livelihoods “breeds domestic violence” where women have few resources. In short, displacement and resource loss magnify gendered risks: when women are crowded into camps or rural camps become isolated by floods, their protection is grossly inadequate.

Environmental Degradation and Food/Water Insecurity

Environmental harm in Kivu compounds climate shocks. Rampant deforestation – whether for charcoal, agriculture, or mining – has steepened hillsides around Goma and its hinterland, intensifying landslides during rains. Mining itself pollutes rivers and gobbles forest, destroying traditional food gardens and medicinal forests that women rely on. Conflict and unsustainable logging have left many communities with eroded soil and fewer fish or game. Without trees to anchor water cycles, Goma’s droughts and floods both worsen. A ClimSA study finds that “deforestation… has resulted in widespread soil erosion around Lake Kivu, contributing to an increasing risk of landslides.” Drought in savanna zones drives pastoralist herders into formerly farmed areas, leading to conflicts with farmers (similar to Kenya’s pastoral lands).

As a result, women face acute food and water insecurity. Agricultural yields are unpredictable and often insufficient. In IDP camps, fields are distant or unusable; many families rely on aid or charcoal sales (the latter requiring hazardous forest treks). Water contamination and lack of sanitation breed disease – diarrheal outbreaks are common after floods. Lack of rainwater capture or irrigation means women often carry heavy jerrycans from distant wells. In these conditions, a single climate shock – even a “normal” rainy season – can tip households into hunger.

Despite these challenges, communities show resilience. Women’s cooperatives and NGOs have begun introducing adaptive practices (though slowly). For example, the “Women in Action” program in Kivu is promoting nature-based solutions – e.g. reforestation, rainwater harvesting and agroforestry – to buffer climate impacts. It works to improve women’s rights to land and finance, so female farmers can plant hardy bean varieties and restore forest margins. Likewise, local groups (such as Pilier aux Femmes Vulnérables and Diobass au Kivu) train women in agroecology, solar cooking and income-generating skills. Community radio and schools are used to spread early-warning messages on storms and health risks. These grass-roots efforts show women leading adaptation: SIPRI notes that in eastern DRC “women actively contribute to… conflict resolution and foster peace,” including by organizing sustainable agriculture, reforestation or clean energy projects. Support for such local, women-led initiatives – from water projects to land rights campaigns – is a key resilience mechanism.

Legal and Policy Frameworks

National and international laws recognize many of these gender and environmental issues, but gaps remain in implementation. The DRC Constitution and treaties create a strong formal basis: Article 13 explicitly bans discrimination on grounds including ethnicity and minority status, and mandates equality of opportunity. Article 14 obligates the state to eliminate discrimination against women and protect their civil, political, economic and social rights; it even guarantees parity in public institutions and criminalizes violence against women. Sexual violence used to “destabilize or displace” communities is classified as a crime against humanity. The preamble explicitly reaffirms commitment to the African Charter and “UN Conventions on… the Rights of Women” (CEDAW). In practice, however, enforcement is weak – pervasive land inequality and impunity for attacks on women (especially minorities) undercut these guarantees.

Key international frameworks further obligate the DRC to protect minority and female rights under climate change:

- CEDAW (1979; rat. 1986): DRC ratified the Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women, requiring laws and policies to ensure women’s equal status. CEDAW’s provisions on women’s participation in development and protection from violence should inform DRC’s climate adaptation and gender policies.

- UNFCCC and Paris Agreement (2015; DRC ratified 2017): As a Party, DRC must integrate gender and human-rights considerations into its climate actions. The Paris Agreement urges Parties to respect “human rights… including gender equality” in all climate policy. DRC’s Nationally Determined Contributions and Adaptation Plans (2015, updated 2020) call for community-based adaptation, though they lack strong gender-specific measures. DRC’s Paris ratification (Dec 2017) means it must now report on implementation of gender-responsive climate strategies.

- African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (1981; ratified 1986): The Charter guarantees the right to a “satisfactory environment” and outlaws discrimination. An African Court advisory opinion (in progress) may soon clarify states’ climate obligations under this Charter. Although the AU’s Maputo Protocol (1995) on women’s rights includes provisions for protecting women in disasters and ensuring land rights, DRC has been slow to implement it fully.

- Domestic Environment Laws: DRC’s 2011 Environment Law (Loi 011/2002) and National Adaptation Plan oblige environmental protection, but often do not address gender explicitly. The government has also established a Ministry of Gender and Action Plans, yet funding and coordination remain inadequate.

Overall, the policy framework explicitly recognizes women’s rights (even in conflict contexts), but climate justice demands more integration. Donors and civil society note that strategies on climate, security, and gender must be aligned (e.g. Germany’s “Feminist Foreign Policy” linkage). Increased enforcement of women’s land rights (parity in agriculture), land redistribution, and climate finance for female-led adaptation would help honor DRC’s legal commitments.

Comparative Perspectives

South Kivu: Similar dynamics play out in neighboring South Kivu. Intense floods in Uvira (2020) and ongoing rains in Sud-Kivu (late 2023) have destroyed villages and farmlands, with women and girls bearing the brunt. Relief groups report that, as in North Kivu, women in South Kivu are often the last to evacuate and suffer most from loss of livelihoods. In 2023 alone, South Kivu floods affected thousands (e.g. 8,400 people in Fizi), with shattered homes and bridges. NGOs emphasize that displaced women there adopt harmful coping strategies (early marriage, prostitution) under food scarcity, mirroring Goma’s crisis.

Kenya (Northern): Pastoralist regions in Kenya offer a broader comparison. There, prolonged drought has similarly forced rural women to travel further for scarce water and firewood. A Plan International study notes that Kenyan pastoralist girls now walk much longer distances – increasing exposure to harassment and violence – after losing livestock to drought. Like in Goma, women’s exclusion from decision-making leaves their knowledge and needs unaddressed. Both regions illustrate how climate shocks overlap with traditional gender roles: women’s unpaid labor (fetching resources, caring for children) increases sharply under environmental stress, often with little support or protection.

Conclusions and Recommendations

In Goma and surrounding areas, climate injustice is manifestly intersectional: marginalized ethnicity, gender, poverty and conflict collide to deprive minority women of safety, resources and dignity. Recent data paint a stark picture – e.g. hundreds killed in floods, nearly 600,000 displaced around Goma (a record high) and a five-fold spike in GBV. Locally-led solutions (women’s cooperatives, agroforestry projects, early warning networks) offer hope, but require urgent support. Policy measures should enforce women’s constitutional rights (land parity, anti-GBV laws) and channel climate funds into gender-sensitive adaptation. International actors must push for the DRC to fully implement its CEDAW and Paris commitments, and to ratify relevant protocols (e.g. Maputo on women’s rights). At the continental level, African courts are beginning to recognize climate justice as a human right under the African Charter – a legal development DRC should embrace to protect its women and indigenous peoples.

Overall, climate justice in Goma means ensuring that women from minority communities have equitable access to land, water and decision-making, and are protected from violence whether they are refugees, farmers or forest dwellers. This requires integrating gender and minority perspectives into humanitarian relief, development planning, and peacebuilding. Only by explicitly addressing the compounded vulnerabilities of these women – through law, policy and practice – can DRC move towards a more just and resilient future for Goma’s marginalized communities.

Featured image: Credit: Abubakari W Kafumba on Unsplash. Infographics by Aarya Dhital, Research Consultant & Specialist on South Asia at Global Divide.