Between 2020-2022, dozens of Indian muslim women-journalists, students, and even pilots, found themselves ‘auctioned’ on apps like Sulli Deals and Bulli Bai. What began as anonymous online trolling quickly became a campaign of public humiliation: islamophobic slurs, doxxing, job risks, and an exhausting loop of police complaints that led nowhere.

This atmosphere defines the reality faced by Rana Ayyub, one of India’s most prominent Muslim woman journalists. In February 2022, UN Special Procedures experts urged India to stop the ‘relentless misogynistic and sectarian attacks’ against her. Days later, she was stopped at Mumbai airport and prevented from boarding her flight to London, where she was due to speak about press freedom. She was served with a summons by the Enforcement Directorate over fundraising.

However, critics contend that the case was less about financial scrutiny and more about weaponizing the state against an outspoken critic of the Bharatiya Janata Party(BJP). India dismissed the UN criticism as ‘baseless and unwarranted’. But, the UN statement made one truth clear: online vilification and legal-bureaucratic pressure often work hand-in-hand, and minority women carry the heaviest burden.

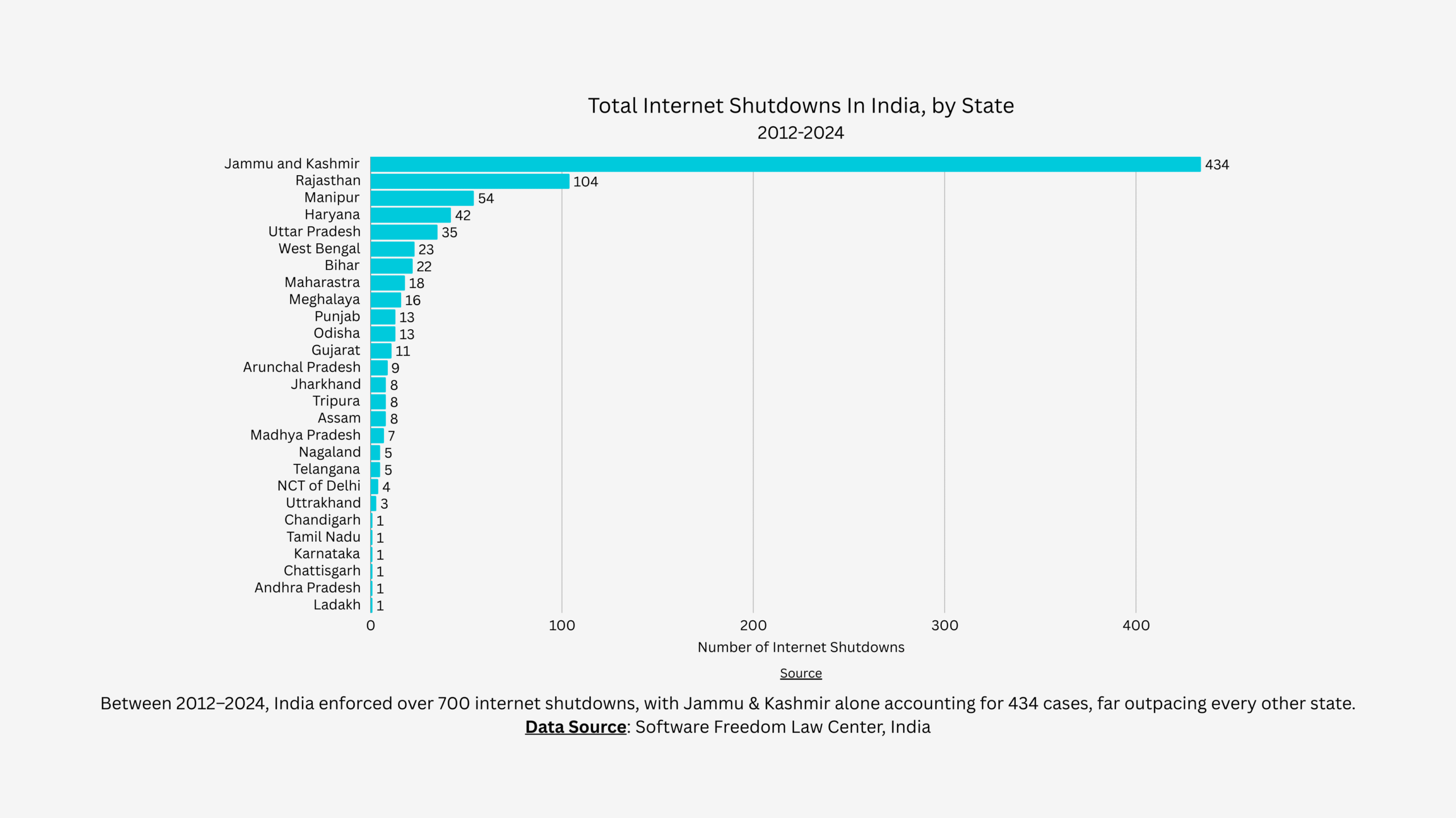

Even the world’s top-ranked press freedom countries such as France, Germany, and Sweden, still struggle with media pluralism due to ownership concentration, political interference, and threats against journalists. But India’s position at 159/180 in the 2025 World Press Freedom Index, places it among the worst globally. Routine internet shutdowns to curb protests, control communal unrest, or even regulate exams have become a powerful silencing- India leads globally, with 736 shutdowns between 2012 and 2023. In 2023 alone, it enforced a 212-day blackout in Manipur, disproportionately affecting women and Dalits.

Unlike Norway (Rank 1), India lacks any statutory recognition of source protection, leaving reporters vulnerable to coercive disclosure. Norway also relies on strong institutional oversight. The Norwegian Press Council, which includes both journalists and members of the public, handles complaints and does so independently, without government interference. Conversely, the attempted establishment of a government-run Fact-check Unit in 2019, even though later struck down by the Bombay High Court, illustrates how preemptive censorship can be institutional. This unit would have allowed authorities to label criticism of government affairs as ‘fake’ or ‘false’, compelling removal without judicial review.

In the United States, Pew research shows that especially young women are more likely than men to face sexualized harassment and stalking online. Black teenagers experience race-based targeting at nearly twice the rate of their white or Hispanic peers, highlighting how intersecting identities such as gender, race, religion, or caste heightens exposure to online harms, a pattern that resonates strongly with the Indian experience.

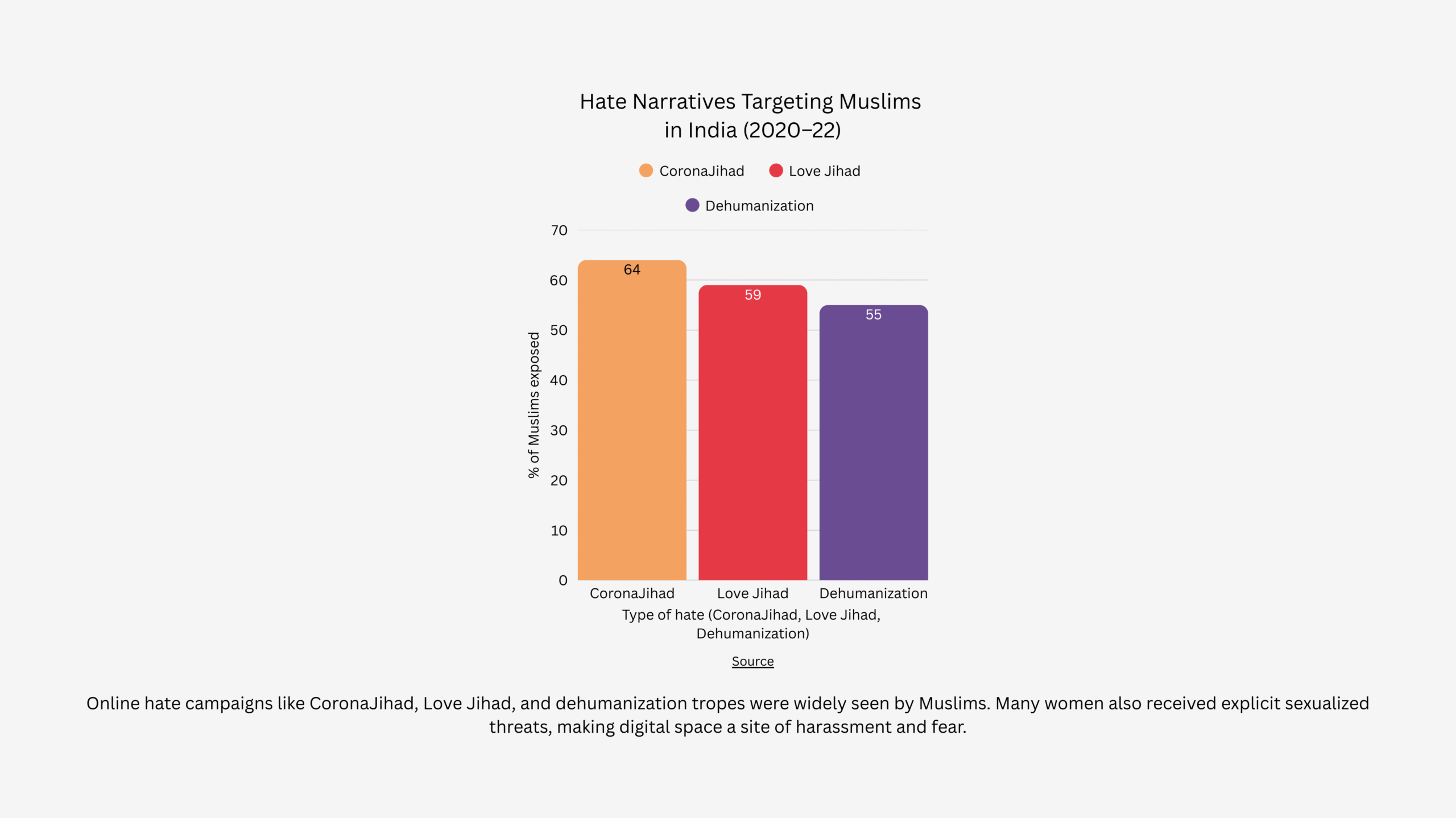

“CoronaJihad: After a Tablighi jamaat gathering, Muslims were branded as ‘super spreaders’.’ Hashtags like #CoronaJihad spread widely, and 64% of Muslims reported seeing this content. Offline, many faced denied treatment, attacked, and barred from selling goods.

Love Jihad: 59% of muslims reported encountering posts alleging that Muslim men target Hindu women, a narrative echoing Europe’s ‘Great Replacement’ theory.

Sexualized hate: Muslim women in India receive explicit rape threats online, including ‘laws’ circulated that prescribe rape as a nationalist duty.

Dehumanization: 55% of muslims reported seeing content comparing them to pigs and dogs, a genocidal trope that primes audiences for violence.”

The misuse of surveillance tools is a global phenomenon. In Saudi Arabia, the Absher app was used by male guardians to monitor and keep track of women’s foreign travels.

Parallelly, in India pegasus spyware was deployed not just against mainstream journalists but also Dalit activists like Bela Bhatia and several lawyers who defeated Dalit communities facing caste violence. For Muslim and Dalit women dissenters, surveillance turns their phones into tools of control, intensifying the religious, caste, and gender-based hostility they already face.

Digital surveillance has turned the lives of Dalit women into a landscape of caste oppression, control, and constant vulnerability. One such example is the use of wearable surveillance tools for sanitation workers, many of whom are Dalit women. Fitted with smartwatches embedded with cameras and GPS, these devices transform into de facto shackles. Workers report avoiding basic functions like bathroom breaks to evade intrusive recording, capturing a deeply dehumanizing form of oversight.

Yet, even as digital tools are deployed to surveil, they also become lifelines. Platforms like Dalit Camera, a pioneering YouTube channel founded in 2011 by Ravichandran Bathran, highlighted struggles beyond the silenced mainstream. Despite being taken down over alleged copyright claims, the channel’s restoration and continued growth underscores the resilience of dalit media activism. #DalitWomenFight, led by AIDMAM since 2013, uses digital platforms to empower Dalit women, document their struggles, and build solidarity with global movements like #BlackLivesMatter. In rural media, Khabhar Lahariya, an all-female Dalit newsroom featured in Writing With Fire, shows how Dalit women harness digital tools to tell their stories and challenge marginalization.

These empowerment efforts stand in stark contrast to the state’s punitive measures; online harassment, Pegasus spyware, internet shutdowns, and attempts at government-controlled censorship. Dalit and Muslim women must prove their marginalization to be recognized, yet remain vulnerable to misrepresentation. Despite this, their resistance creates a powerful counter-narrative; when marginalized communities control digital and community media, these platforms become tools of empowerment rather than silencing.

Singapore has built one of Asia’s strongest data protection regimes. Its Personal Data Protection Act requires every company to appoint a data officer and subjects them to real penalties if they fail. The regulator is not just symbolic-it can issue binding orders and impose fines that bite. This could be an example for India on how accountability can be built into the system itself, leaving less room for state or corporate abuse.

Likewise, The Philippines’ National Privacy Commission is widely respected as one of the most independent in the region. With quasi-judicial powers to investigate, sanction, and shape national policy, its existence proves that regulatory independence in Asia is not just aspirational, but possible.

India, by contrast, designed its Data Protection Board of India to sit firmly under government control. Members are appointed and removed by the executive, its powers are narrowly adjudicatory, and it lacks meaningful autonomy. The consequence is stark: the very authority tasked with protecting privacy is structurally aligned with those most likely to violate it. Dalit and Muslim women, who are disproportionately targeted by online harassment and state surveillance, face this gap most acutely. Without an independent regulator, there is no neutral mechanism to hold perpetrators accountable or prevent digital abuse from being weaponized against them.

Recommendations

1. Whistleblower Protections as Shields for Dissent

The EU Whistleblower Protection Directive 2009 obliges organizations to create safe internal and external reporting channels and shields whistleblowers from dismissal, demotion, or other reprisals. Member states have been fined for failing to implement it effectively. By contrast, India passed the Whistleblower Protection Act in 2014 but has yet to bring it into force. Without active enforcement, citizens seeking information remain exposed to retaliation.

2. Data Protection: Caste, Religion, and Gender as Special Categories

Under the EU’s GDPR, ethnicity and religion are designated as ‘special category data’ demanding explicit consent, restricted use, and elevated safeguards. India’s Digital Personal Data Protection Act (2023), however, does not treat caste, religion, or gender as sensitive categories, leaving individuals vulnerable to profiling and discrimination.

3. Survivor-Centric Reporting and Community Media

Pakistan’s Digital Rights Foundation runs a toll-free Cyber Harassment Helpline providing legal, digital security, and psychological support to thousands of women each year. India, in contrast, lacks a comparable survivor-centered digital reporting mechanism. What it does have are grassroots initiatives like Sangham Radio in Telegana, the country’s first Dalit women-run community radio, which amplifies marginalized voices but operates with limited funding.

4. Coordinated Civil Space and Global Solidarity

Australia’s eSafety model shows how coordination between platforms, NGOs, and police can deliver survivor-first responses to online harms. Similarly, the Christchurch Call and WeProtect Global Alliance demonstrate how governments, tech companies, and civil actors can jointly counter digital abuses with clear accountability mechanisms. By contrast, India lacks such structured coordination. Building a national framework that also draws on Black Feminist and Indigenous movements’ principles of equity and community control would ensure safeguards against digital surveillance targeting Dalit and Muslim women.

Featured image: Credit: Sankalp Mudaliar on Unsplash. Infographics by Aarya Dhital, Research Consultant & Specialist on South Asia at Global Divide.