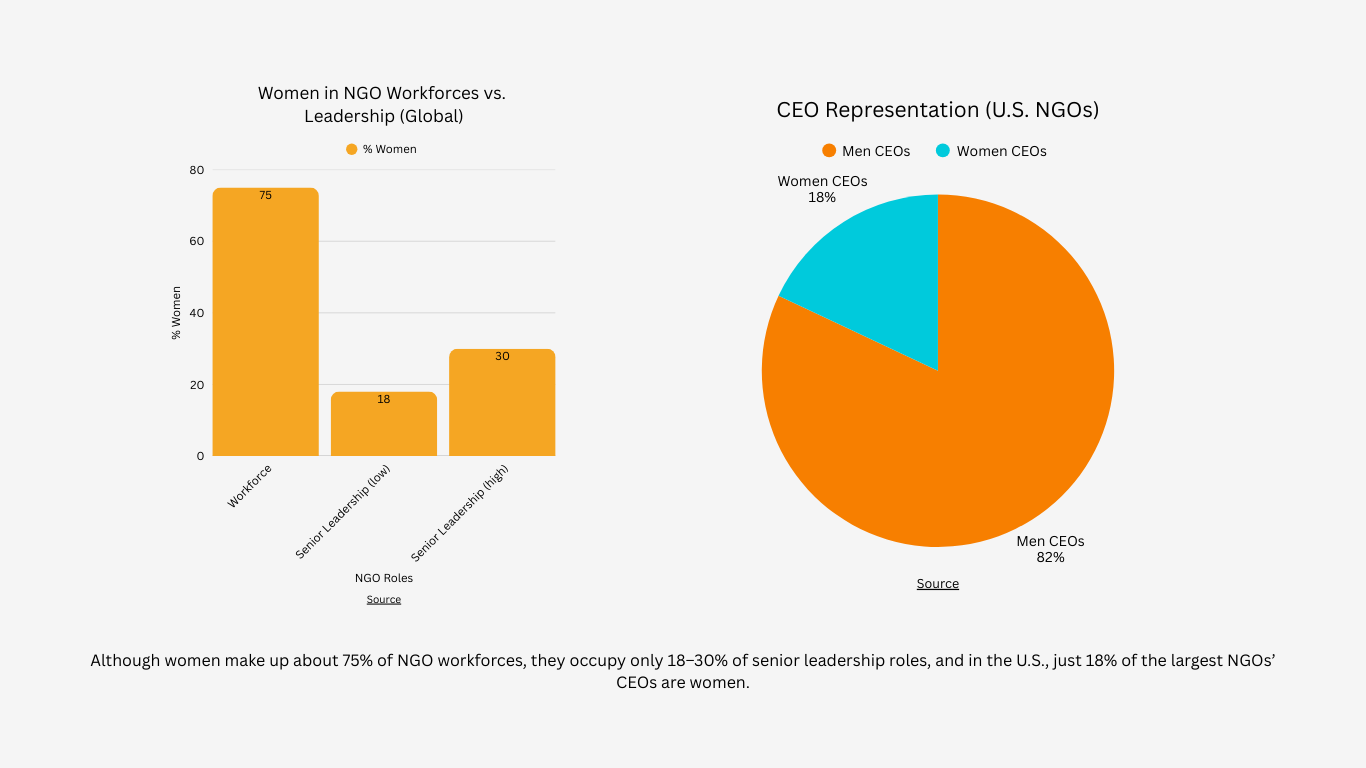

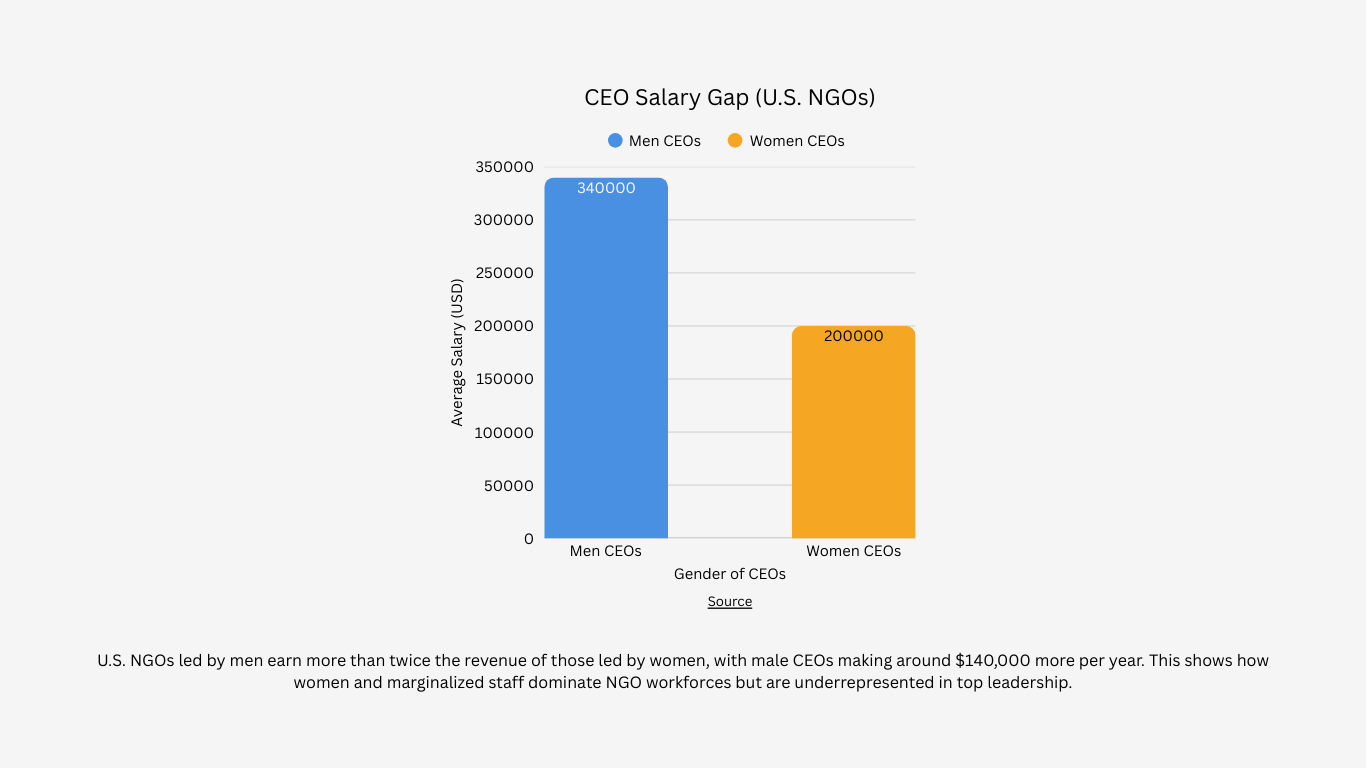

The nonprofit/NGO sector globally exhibits stark gender and intersectional leadership gaps. Women comprise roughly 75% of NGO workforces, yet hold only 18–30% of senior leadership roles. For instance, a US analysis found that while three-quarters of nonprofit staff are female, only 18% of the largest NGOs’ CEOs are women—and those women CEOs earn about 8% less than male CEOs.

A recent report on U.S. NGOs revealed men-led organizations have more than twice the revenue of women-led ones, and male CEOs earn on average $140,000 more annually than women peers. These disparities reflect a classic “glass ceiling” (women stuck below top ranks) and even a “glass escalator” effect where men in female-dominated fields often rise faster. In short, women and other marginalized staff remain overrepresented in NGO labor but underrepresented at the top.

Intersectional Barriers to Leadership

Barriers are not only gender-based. NGOs often mirror societal hierarchies, so intersectional factors further compound who rises to leadership. For example:

- Caste (South Asia): In India’s NGO sector, upper-caste (Brahmin) elites dominate even “social justice” organizations. One study found the development sector is “disproportionately occupied and operated by privileged sections with Brahmanic cultural capital,” sidelining Dalit and Adivasi activists. Caste bias is entrenched: reports cite that even Dalit-focused NGOs sometimes appoint upper-caste CEOs, effectively blocking lower-caste Christians and Dalits from leadership.

- Race/Ethnicity: Globally, people of color and indigenous people face parallel “bamboo ceilings.” Research shows that women of color have similar qualifications and aspirations as white male counterparts, yet remain significantly underrepresented in top NGO positions. Racial bias in hiring, promotion, and donor relations means many Black, Asian, or indigenous women (and men) struggle to reach NGO leadership despite large contributions at staff level.

- Religion and Class: Minority religions or impoverished classes also often lack a voice. In some contexts (e.g. South Asia or the Middle East), NGOs led by dominant religious groups may implicitly exclude minority faiths from leadership. Upper-class bias is also evident: well-educated elites disproportionately occupy NGO boards, leaving grassroots poor communities without representation.

- Sexuality and Other Identities: NGOs rarely track or promote LGBTQ+ people, people with disabilities, or other marginalized groups into leadership. Heteronormative and ableist cultures mean lesbian, bisexual or trans staff – as well as persons with disabilities – often lack mentors and face discrimination. In short, biases of caste, race, religion, class, sexuality, etc. intersect with gender to freeze many capable candidates out of decision-making posts (a phenomenon aptly captured by the term “bamboo ceiling” for Asians and parallels in other communities).

INGOs vs Local/National NGOs

Leadership disparities also vary by organization type. Large international NGOs (INGOs) headquartered in the Global North often centralize power, even when implementing programs in the Global South. Donors and senior management tend to remain dominated by (often white) staff from wealthy countries. For example, local and national NGOs frequently report that well-funded INGO affiliates compete with them for grants and decision-making seats, undermining local leadership. A candid analysis notes that many Southern activists point at INGOs “account[ing] for a disproportionate share of the resources” and decision-making power, creating “an overarching sense of power imbalance between global actors and local actors.”

By contrast, smaller local NGOs in the Global South are often staffed by women and community members and may pursue more participatory governance. However, they usually have far less access to major donor funds and international networks. This can freeze local leaders out of high-level forums: in practice, INGO affiliates with global brand names and bigger budgets often “occupy seats at the table that rightly belong to indigenous groups.” In short, equity remains skewed toward Northern INGOs.

Tokenism and Performative Diversity

NGOs sometimes respond to these inequities with mere symbolic gestures. Tokenism – superficially appointing one or two women or minorities to high-profile roles – is widespread. As one guide explains, tokenism involves “including individuals from underrepresented groups in a way that is superficial or symbolic,” selecting them for their identity without giving them real authority. In NGO practice this can look like appointing a woman to a board seat but keeping male-dominated management in charge, or creating a “women’s advisor” role with no power. Performative diversity takes this further: organizations issuing public commitments to gender equity or diversity training, yet failing to change hiring or promotion systems. These tactics allow NGOs to claim progress while the deep culture and power structures remain unchanged.

Impact of Leadership Gaps on NGO Work

The consequences of homogenous leadership reach beyond HR charts. When boards and executives lack diversity, NGOs risk becoming disconnected from the communities they serve. As one analysis warns, a leadership team that “lacks diversity… risks becoming disconnected from the communities it serves,” and this “disconnect can lead to failure to address the unique needs and perspectives of marginalized groups.” In practice, male-majority leadership may design programs blind to women’s practical realities (e.g. needing childcare or respect for local customs). Policies on education, health or rights crafted without women’s and minority input often miss key barriers facing half the population. Similarly, without ethnic or religious representation, NGOs may inadvertently exclude or alienate segments of the community.

These disparities also hurt NGOs’ credibility and funding. Funders and local stakeholders increasingly expect nonprofit teams to reflect those they help. Data show women-led NGOs often receive less funding than similar men-led ones. This funding gap partly stems from donor bias – donors may subconsciously trust male leaders more – and from networks that favor familiar (often Northern male) names. The result is a vicious cycle: underfunded women/minority-led NGOs cannot scale, reinforcing stereotypes about their capacity. In sum, lack of inclusive leadership both skews program relevance and undermines NGOs’ overall effectiveness.

Case Studies and Reform Examples

Despite the challenges, some organizations and contexts show progress. In the humanitarian field, Oxfam International’s “global balance” initiative is often cited. Since 2008 Oxfam has transformed from a Northern-centric network into a confederation with affiliates in the Global South (India, Mexico, Brazil, Turkey, Colombia, South Africa, etc.). Leaders from these affiliates now sit in Oxfam’s highest leadership bodies, deliberately bringing “new voices, opinions, and ways of working” to the table. Oxfam’s executive leadership openly commits to ensuring its newly national affiliates have a net positive effect on local leadership, signaling a move away from the old “colonial” model of aid.

Similarly, UN Women and feminist donors have boosted networks of women’s rights NGOs. With targeted grants and mentoring, many grassroots women-led NGOs have grown in influence and professionalism. For example, UN Women reports that support to women-led groups in India and Kenya enabled organizations to expand vocational training and legal advocacy programs at scale. These cases underline that when women and marginalized people run NGOs (and receive resources and training), outcomes can be powerful and relevant to beneficiaries. In the private sector, some companies have adopted gender quotas and leadership pipelines (e.g. 40–50% targets for female executives) – a model civil society could emulate. Likewise, feminist networks (e.g. Asia Pacific Forum on Women, Law & Development or African Women’s Development Fund) share governance best practices and press for parity, creating success stories of inclusive leadership.

Best Practices and Recommendations

To close leadership gaps, NGOs should adopt structural reforms and concrete targets:

- Set measurable targets and transparency. NGOs (and funders) must collect and publish disaggregated data on leadership by gender and other identities. Boards and management teams should be held to targets (e.g. 50% women, representation of local nationals, etc.), similar to corporate “women on boards” laws. Requiring public gender/diversity reports can drive accountability.

- Shift power to the local. INGOs should implement “power-shifting” policies: channel more decision-making and funds to Southern partners, transition leadership roles to qualified local staff, and form governance boards that include host-country stakeholders. The Oxfam model shows it is possible to create nationally registered affiliates with local leadership while still sharing technical resources globally. Donor policies (like the Grand Bargain localization commitments) should enforce that funding flows through local NGOs and women’s rights organizations, not just Northern pipelines.

- Build diverse pipelines. Mentorship, training and promotion programs should prioritize women and marginalized staff. For example, establish leadership cohorts of female managers, provide executive coaching on unconscious bias, and create sponsorship programs pairing senior mentors with high-potential women/minority employees. Earmarked fellowships or leadership academies for underrepresented groups can counteract entrenched networks.

- Cultural change and inclusion. Organizations must go beyond one-off workshops to root out sexism, casteism, etc. in workplace culture. This includes enforcing zero-tolerance on harassment, enabling flexible work for caregivers (so women are not penalized), and valuing diverse leadership styles. Hiring committees should be diversified and trained to spot and counter bias. Adopting co-leadership models (shared authority between men and women) is one example of feminist practice.

- Equitable funding. Donors should tie grant criteria to leadership diversity: NGOs led by women or local actors should be actively sought and supported. Funds should be earmarked for grassroots and identity-based organizations. Within large NGOs, budget allocations can be reviewed for equity (do male-led projects get more funds?). This helps level the playing field so that inclusive organizations have resources to grow.

Overall, reform must come from both within NGOs and from external pressure. When organizations “walk the talk” on gender and diversity – not just in words but in Board composition, leadership hires, and funding flows – the sector’s programs become more credible and effective. As one NGO analyst concluded, NGOs must “embrace diversity to transform power dynamics,” ensuring that whose voices are in charge truly reflect the world those NGOs aim to serve.

Featured image:Credit: Akeyodia – Business Coaching Firm onUnsplash. Infographics by Aarya Dhital, Research Consultant & Specialist on South Asia at Global Divide.