Indian gender justice frameworks often profess progressive aims, but critics argue they overlook intersecting oppressions. Many national schemes and laws focus on “women” as a monolithic category, failing to account for caste, class, religion, or sexuality. For example, Nirbhaya Fund allocations (in response to the 2012 Delhi rape) have been widely criticized as ineffective: by 2019 nearly 90% of its ₹3,600 crore corpus remained unspent. No state had used over half of its allotment, and Maharashtra spent virtually nothing despite high crime rates. Such data suggest a gap between rhetoric (funds for “women’s safety”) and reality. Meanwhile, the Maternity Benefit (Amendment) Act 2017 extended formal-sector leave from 12 to 26 weeks – a welcome change in theory – but its design (where employers bear all costs) has had unintended effects. A recent analysis found the reform reduced employment and incomes for prime-age women, as firms became less willing to hire women of childbearing age. Poor women outside the formal sector remain entirely excluded from these benefits, deepening existing inequalities.

The 2019 Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act similarly drew fire for sidelining intersecting identities. It was drafted without consulting trans activists and lacks provisions recognized by the Supreme Court (such as affirmative action). When the government proposed extending reservations to trans persons, it simply added them to the broad OBC quota – in effect erasing caste diversity among trans people. Activists warned that a Dalit trans person would be forced to choose between gender- and caste-based quotas, “possibly depriving them of a chance at greater visibility and voice.” Advocates successfully campaigned for horizontal reservations (separate slots for trans within each caste category), but the episode underscores how policy often treats “women” or “trans” as undifferentiated groups, ignoring intersecting needs.

Institutional Responses and Marginalized Women

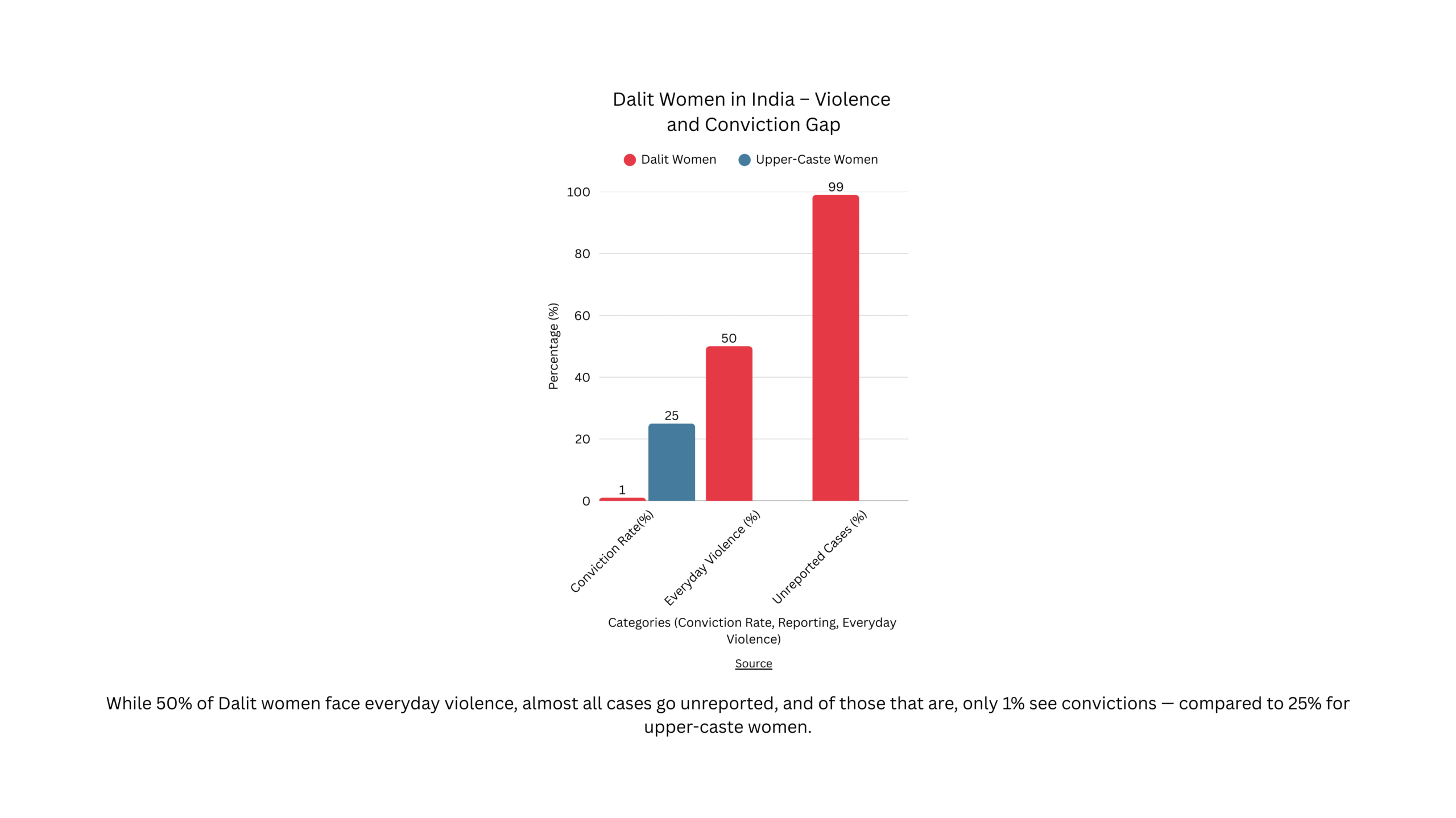

In practice, law enforcement and justice systems in India frequently reflect caste and religious biases. Dalit women’s experiences illustrate this starkly: in Haryana, for instance, Swabhiman Society and Equality Now found sexual violence is used by dominant castes to oppress Dalit women, under a pervasive “culture of violence, silence and impunity.” Dalit survivors reported that convictions are rare – one review of criminal records notes “less than 1%” of Dalit women’s rape complaints result in conviction, versus 25% for upper-caste victims. Many Dalit women fear or distrust police and courts: over 99% of caste-based sexual assaults go unreported.

Institutional failures compound these barriers: for example, special women’s courts and helplines exist under central schemes, but reports suggest they are underutilized or inaccessible to poor and rural survivors. Specialized bodies like the National Commission for Women (NCW) often appear out of touch with marginalized constituencies. During 2023–24, eight of ten NCW inquiries into crimes took place in opposition-ruled states, while crises in BJP-ruled regions were ignored. NCW Chair Rekha Sharma was widely criticized for going silent on cases involving tribal and rural women (such as the Manipur violence against Kuki women) while speaking out on politicized issues like “love jihad.” Such episodes fuel the perception that institutional “gender justice” bodies can become mouthpieces for powerful interests rather than champions of all women.

The criminal justice system too shows intersectional blind spots. As scholars note, caste and class hierarchies shape policing and prosecution. One analysis echoes Dalit activists’ critique of the #MeToo era: why did a separate #MeToo campaign emerge in India “even when [Raya] Sarkar’s list wasn’t only for Dalit women?” Mimi Mondal asks, “why are Savarna Indians so reluctant to be represented by a Dalit woman? What message does that send to us Dalit women?” Here “Savarna” (upper-caste) capture of feminist spaces meant that mainstream gender-justice efforts often sideline caste issues. Likewise, an Equal Opportunity Panel for students or workplaces may exist on paper, but in practice Dalit, Adivasi or Muslim women reporters seldom see their unique grievances addressed.

Across rural India, intersecting oppressions are particularly acute. Dalit and Adivasi women are frequently landless laborers or manual scavengers excluded from labor protections. They are often housed in segregated hamlets on village peripheries, lacking sanitation and transport. Adivasi women historically held relative autonomy and forest knowledge, but mining and development have disempowered them; today many are displaced and impoverished by land grabs. Even when laws exist (e.g. land or forest rights for tribals), enforcement is patchy. Within Adivasi communities, gender norms vary, but one study notes that better-off OBC women sometimes assert themselves as “superior to Adivasis,” dominating local gatherings. Thus poor tribal women face patriarchy in their own communities as well as discrimination from outsiders, a double burden seldom acknowledged in national policymaking.

Urban women, by contrast, more often confront issues like workplace harassment, transportation safety and sexual violence in public. Schemes like the Nirbhaya Fund emphasize CCTV, helplines and legal aid in cities, but activists argue these measures can feel tokenistic. City-based feminist groups do highlight many women’s issues – but they too skew toward middle- and upper-class participants, leaving working-class, Dalit or minority women underrepresented. As one Dalit queer activist recalls, in many Delhi LGBT forums “people would only converse in English… we never talked about” caste, because most members were affluent, upper-caste Indians. In such spaces, Dalit and OBC women’s voices are “token gestures,” only highlighted externally to suggest inclusivity, while real decision-making remains in upper-caste hands.

Feminist Movements and Intersectionality

Major feminist mobilizations in India reflect these divides. The 2018–20 #MeToo India wave (online and media campaigns exposing harassment) was dominated by urban professionals, and largely remained within savarna circles. Critics charged that mainstream #MeToo largely ignored Dalit and working-class survivors. As Mimi Mondal aptly asked, why did Indian feminism need “a new, unrelated #MeToo movement” to discuss sexual harassment on a mass scale when Savarna-led feminism already existed – and what “message does that send to Dalit women?” Indeed, Dalit women’s collectives and some academics called for an anti-caste lens on #MeToo: in many cases (as in the 2014 Hathras gang-rape), caste played a central role but rarely featured in national discourse. By contrast, some grassroots groups emphasized caste and class. For example, the 2018 viral “#DaminiKiMehfil” series included Dalit voices recounting rape by upper-caste men, and academics pointed out that Dalit women’s complaints face far greater social stigma and legal hurdles.

The student-led Pinjra Tod (“Break the Cage”) movement (from 2015 onward) sought to challenge dormitory curfews and patriarchal campus rules. Officially it billed itself as an “intersectional” collective, explicitly opposing “Brahminism, fundamentalism, [and] domination of ‘Savarna’ elite women.” It included some leaders from diverse backgrounds and even staged plays celebrating icons like Savitribai Phule and Fatima Sheikh. Yet insiders have since spoken out that Pinjra Tod’s internal culture often fell short of its ideals. Marginalized members reported feeling tokenized: Dalit, OBC and Muslim participants say they were called upon only when needed “to be seen” in the group, while a small core of upper-caste women made most decisions. Unaddressed demands (e.g. for quotas in elite college hostels) led some Bahujan students to disengage. These debates suggest that even progressive student movements can mirror social hierarchies unless they explicitly share power.

The 2019–20 Anti-CAA/Anti-NRC protests offer another contrast. Unlike #MeToo, these were led by religious minorities and secular allies rather than by a feminist leadership. One prominent example was Shaheen Bagh in Delhi, where Muslim women organized a months-long sit-in against the Citizenship Amendment Act. Scholars note that Shaheen Bagh became “a powerful symbol of resistance against…exclusionary nationalism” precisely because it was led by women from a Muslim-majority neighborhood. Rather than a narrow “women’s issue,” these protests invoked gendered claims of citizenship and dignity: the women protesters were portrayed as protectors of their community’s future. In that sense, Shaheen Bagh and similar protests were highly intersectional – rooted in both gender and religion (and some class). National women’s organizations and celebrities had varied responses: some joined the chorus, emphasizing secular solidarity, while others (especially those aligned with the ruling party) painted the protests as merely communal. Either way, mainstream feminist discourse paid little attention to the needs of Muslim women beyond solidarity slogans.

Beyond these headline movements, grassroots feminist organising often fills gaps left by national structures. Dalit feminist networks (e.g. Dalit Mahila Samiti, Birsa Adimjati Mahila Sangathan) have long documented caste-specific abuses and demand reforms like expedited trials under the SC/ST Atrocities Act when gender violence overlaps with caste atrocities. Tribal women’s cooperatives (such as Self-Help Groups in Jharkhand) sometimes create their own dispute-resolution forums, as seen when women united to shut down illegal liquor shops affecting villagers. Queer and trans activists (like the Trans Rights Now Collective) have campaigned for inclusive reservation policies and against forced medicalization. Across contexts, grassroots leaders critique token gestures by elite institutions. For example, Dalit trans activists note that while LGBT pride marches (like Delhi Pride, pictured) draw colorful crowds, caste and class remain taboo subjects in these spaces. Muslim women’s rights organizations (such as the Bhartiya Muslim Mahila Andolan) have conducted their own surveys to inform secular courts and governments about triple-talaq and domestic abuse. These groups underline that policy must be informed by diverse voices – a point often neglected by top-down schemes.

Urban–Rural and Regional Variations

Gender justice in India also varies sharply by geography. Urban areas tend to have more visible activism and infrastructure (women’s NGOs, rape crisis centers, news coverage), but also high cost of living and commodification of feminist discourse. For instance, NCRB statistics often show higher crime reporting in cities, but much of that reflects greater awareness and activism rather than safer conditions. In rural regions, women may face entrenched caste councils and police inertia. Adivasi women in Jharkhand often rely on village assemblies to resolve spousal abuse, as formal systems may be far away. Thus while women’s rights clinics exist in cities, a woman in a remote tribal village might never see a lawyer. Schemes like the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) have empowered millions of rural women economically, but even there benefits differ by caste: landless Dalit and Adivasi women make up a large share of MGNREGA laborers, and yet they face the same landlord-colleague harassment as in non-schemed jobs.

State-level differences are prominent too. Some states have been proactive: for example, Kerala and Bihar banned triple talaq before the 2019 national law, and Tamil Nadu provides more than 50% reservations for women in local bodies. Others have lagged. Use of federal funds for women’s safety (from Nirbhaya Fund) varies wildly: while Uttarakhand reported ~50% utilization, states like Delhi and Maharashtra used almost none. These gaps mirror political will: critics pointed out that despite Maharashtra’s high crime rates it spent zero from the safety fund. More recently, India’s Parliament passed a long-awaited Women’s Reservation Act (2023) promising one-third of MPs be women. However, implementation awaits a new census and delimitation, and it contains no provision for OBC women. Observers warn that without addressing sub-categories (caste, class, religion), even this broad measure may not translate into real power for the most marginalized women.

Urban-rural divides also affect movement participation. Movements like #MeToo or Pride see heavy metropolitan turnout, whereas rural and small-town women often engage through localized struggles (e.g. campaigns against manual scavenging, or campaigns for school safety after high-profile cases). The pinjra tod protests of Delhi didn’t resonate in rural universities, where student life follows different rhythms. Conversely, rural women’s collectives (like Mahila Arogya Samitis) speak less on national feminist issues but fight everyday problems (health, water, school dropouts).

In sum, India’s formal gender-justice agenda has expanded greatly in the past decade – from harsher criminal laws for rape and sexual violence to large budgets for women’s schemes. But a critical review finds that many policies remain tokenistic toward intersectional realities. Institutional actors often treat gender as a single axis, obscuring how caste, religion and sexuality compound women’s oppression. As activists note, being “savarna” or city-based often means dominating the agenda, while Dalit, Adivasi, Muslim, trans and poor women struggle to be heard. Major campaigns have made space for some cross-cutting issues (Shaheen Bagh bridged gender and citizenship; trans activists raised caste within queer rights), but these remain exceptions.

Moving forward, experts argue for genuinely intersectional policy design: resources for Dalit women’s shelters, recognition of horizontal reservations for subaltern women, inclusive curricula on gender, caste and secularism, and accountability for how funds reach marginalized communities. Grassroots alternatives – from village women’s sangathans to Dalit feminist networks – provide models. As one Dalit scholar concludes, “the erasure of [Dalit women’s] suffering…and their leadership…recalls the critical anger which crafted anti-caste resistance.” A truly intersectional feminism in India would heed that anger, centering the voices of the most oppressed rather than leaving them at the margins.

Featured image: Credit: Wandering Indian on Unsplash. Infographics by Aarya Dhital, Research Consultant & Specialist on South Asia at Global Divide.