Sri Lanka’s laws currently do not criminalize marital rape. Under Penal Code Section 363, a husband’s non‑consensual sex with his wife is legal unless the couple is judicially separated. In practice this means married women have no criminal remedy if their husband forces sex, and courts effectively treat women as giving inherent permanent consent within marriage. As one local analysis bluntly noted, “marital rape is no rape in Sri Lanka” under current law. The civil Prevention of Domestic Violence Act (2005) too – which defines domestic abuse as physical or emotional harm by a spouse – provides only protection orders, not criminal penalties, for sexual violence in marriage.

Sri Lanka’s law assumes ongoing consent once a woman is married. This has drawn sharp criticism: a 2021 report notes that Sri Lanka (like India and others) “fails to fully criminalize marital rape, leaving women vulnerable.” UN treaty bodies have pressed Sri Lanka to criminalize spousal rape. In the meantime, very few rape cases are resolved: a regional report found only 3.8% of rape cases in Sri Lanka lead to conviction, reflecting impunity that affects all survivors (including wives raped by husbands). Women’s advocates also point out that police and courts often dismiss spousal abuse or expect evidence of physical resistance, further denying married women justice. Additionally, criminalising marital rape in cases where couples are judicially separated is redundant. A presumed lack of access to a spouse suggests a lack of opportunity to assault, or at the very least a decrease.

Societal attitudes compound these legal gaps. Many Sri Lankans view wife‑obedience as normal: one interviewee said “when a woman gets married… she is, for lack of a better word, obedient to the husband”, and that dynamic makes marital rape “an issue.”

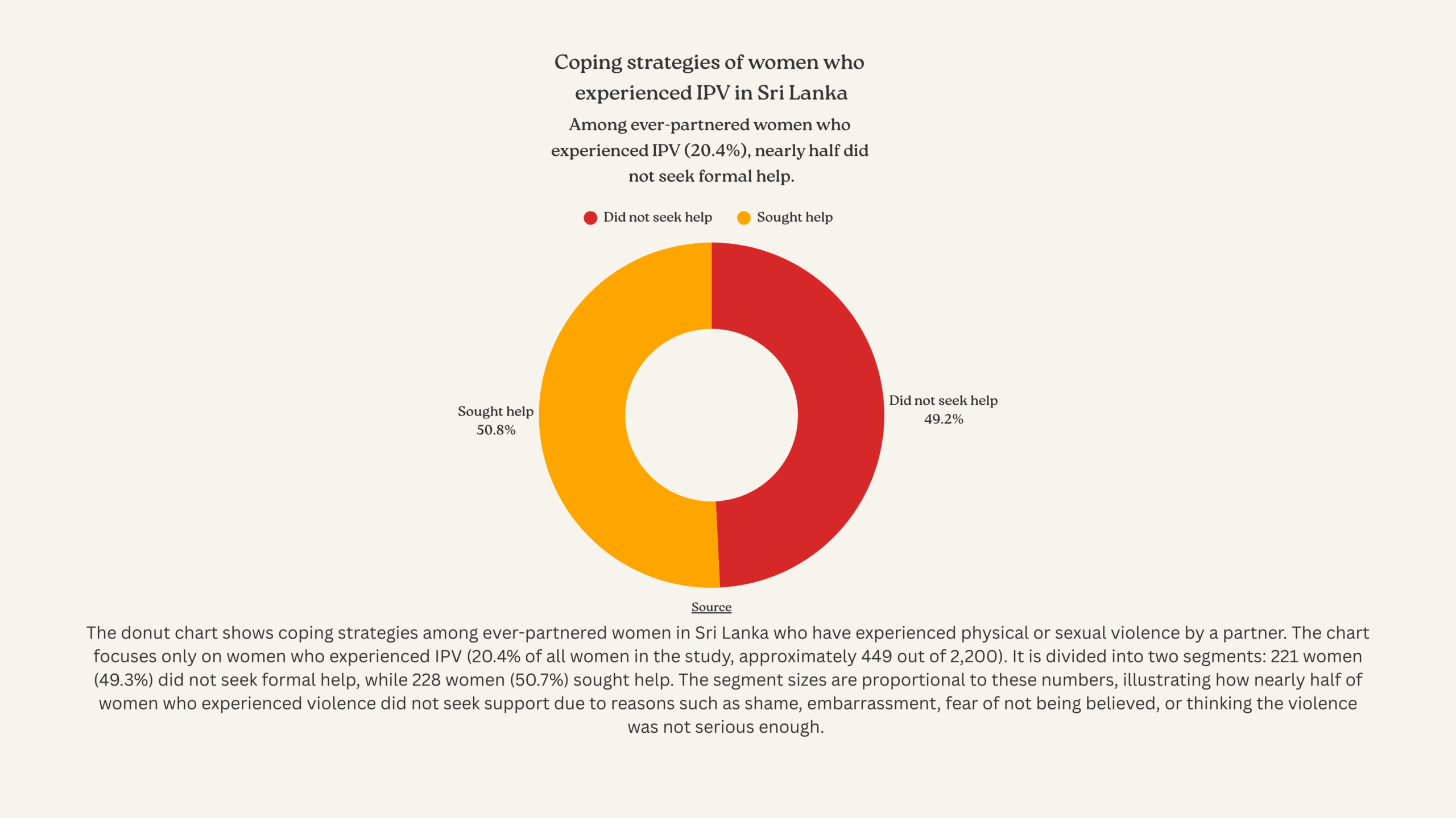

Psychologists and activists warn that patriarchal norms – which see women as property of their husbands – silence victims. As a gender specialist explained, marital rape often stems from “patriarchal structures reinforced by cultural norms” and is considered “a heinous thing” only by those who challenge these traditions. In public discussion, survivors cite fear and stigma: nearly half of Sri Lankan women who experience sexual violence by a partner never seek help due to shame or beliefs that “the violence was normal.” (Indeed, one survey found 20.4% of ever‑partnered Sri Lankan women reported physical or sexual partner violence in their lifetime.) All of this discourages marital rape victims from reporting abuse: they know the law won’t protect them and society may blame them.

Personal Laws and the MMDA: Child Marriage and Consent

Sri Lanka’s personal law for Muslims; the Muslim Marriage and Divorce Act (MMDA) – exacerbates the problem. Unlike general law (which sets marriage at 18), the MMDA historically had no effective minimum age for Muslim girls. In practice it allowed marriages from age 12 (and even younger under religious custom). Equality Now reports that in “Sri Lanka, the MMDA allows child marriage, polygamy, and gender–unequal divorce rights.” A recent analysis highlights that Sri Lanka’s penal law “explicitly permits marital rape of children over the age of 12.” In short, a Muslim girl under 16 can be lawfully married and raped by her husband without legal consequence. This loophole is stark: as activists note, “the law on statutory rape is not applicable to Muslim girls under 16…who are married under the MMDA,” so girls are often married to their rapists and perpetrators escape accountability.

Reform efforts have been slow. Although Sri Lanka’s government agreed in 2019 to raise the MMDA marriage age to 18, the promise stalled: advocates report the amendment bill “is gathering dust in Parliament.” (In 2023 the Cabinet finally allowed Muslim marriages to be registered under the general law, which does require 18 years of age.) Until these reforms take full effect, Muslim women remain legally disadvantaged. For example, under the MMDA a wife cannot even sign her own marriage contract – only a male guardian (wali) can give consent – and a husband can divorce unilaterally (talak) without notice. The cumulative effect is a system where many Muslim women have no legal recourse to challenge forced sex, childhood marriage, or marital abandonment.

Enforcement, Compensation, and Missing Support

Even beyond marriage laws, enforcement of rape laws is weak. In Sri Lanka only about 4% of reported rape cases result in conviction, among the lowest in the region. Victims face obstacles at every step: corrupt officials, victim blaming and a cumbersome court process. Some legal reforms have improved procedure (e.g. requiring consent, and allowing evidence other than physical injuries), but justice is often denied. Sri Lanka does have a state compensation scheme for rape survivors (unlike most countries), but in practice survivors rarely access these benefits. Most critically, marital rape victims fall outside criminal law altogether, so they are typically forced to seek only civil protection orders (under the PDVA) or to petition for divorce. In many cases women choose silence; one study found nearly 50% of women who faced partner sexual abuse never told authorities, citing shame or resignation.

Worldwide experts and UN bodies stress that Sri Lanka must close these gaps. For example, the UN CEDAW Committee and Human Rights Committee have repeatedly urged Sri Lanka to recognize marital rape as a crime. Local activists echo this, emphasising that the state should ask whether it is comfortable with what is essentially state–sanctioned child marriage, and marrying women and girls off to their rapists. In summary, Sri Lanka’s combination of outdated marriage laws, legal loopholes, and patriarchal norms leaves married women extremely vulnerable. Until marital rape is criminalized in all circumstances and personal laws are equalised, women will lack remedies and remain at risk.

Comparative Overview: Marital Rape Laws in South Asia

Legal Status Across the Region

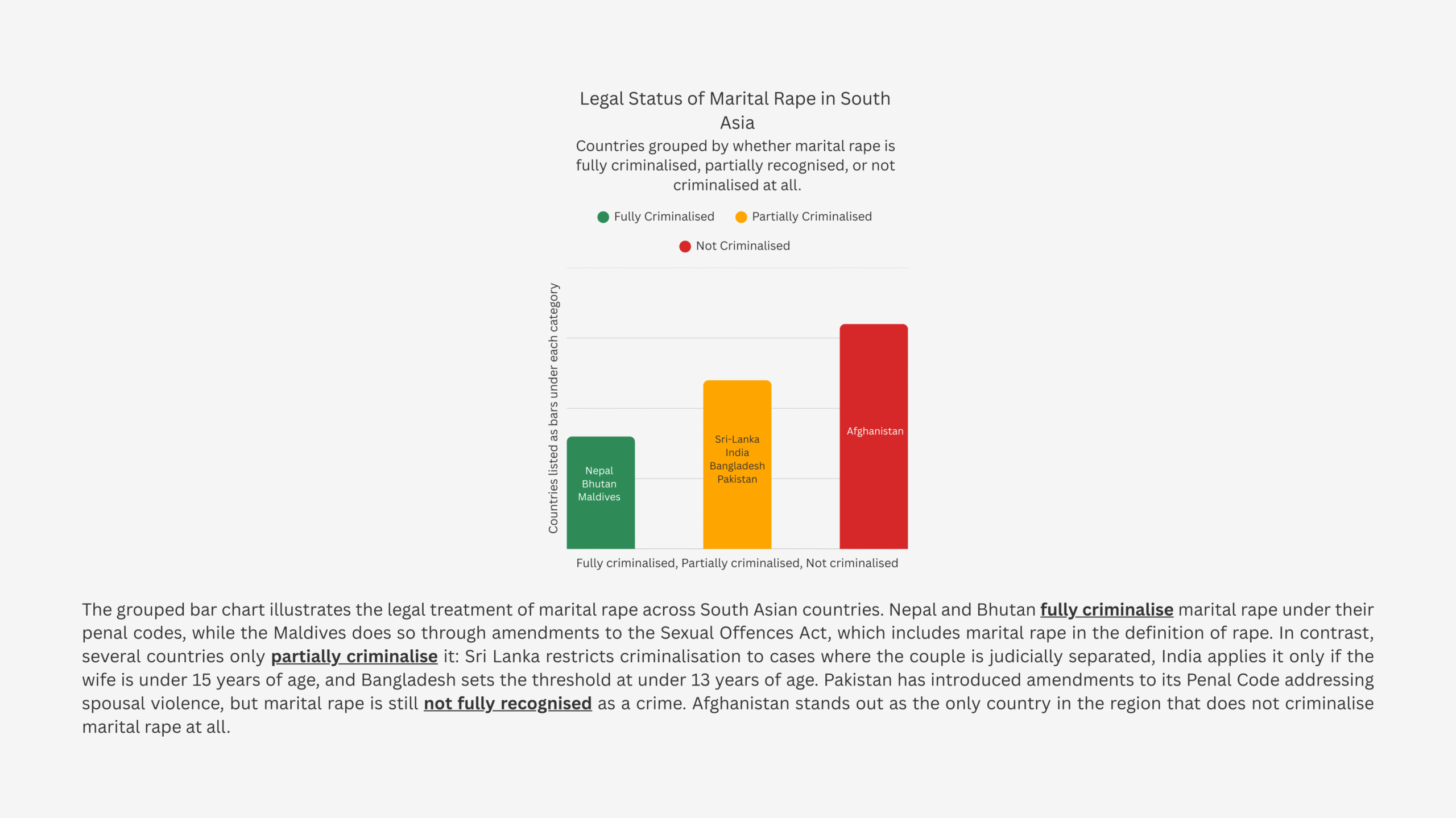

A regional review shows that marital rape remains unrecognized as a criminal offense in most South Asian countries, with only Nepal and Bhutan explicitly criminalizing it. Despite constitutional guarantees against gender–based violence in countries like India and Nepal, traditional patriarchal norms and colonial legal remnants continue to shape the absence of marital rape laws in most local statutes. Scholars highlight the colonial origin of the marital rape exception – rooted in the doctrine of coverture – still enforced in legal frameworks across South Asia, denying married women bodily autonomy. As one legal analyst notes:

“Marriage is interpreted as permanent consent, erasing sexual consent from the legal rubric.”

In societies where shame and stigma are attached to reporting intimate partner sexual violence – and many believe domestic violence is justified for reasons such as refusal to have sex – married survivors rarely seek legal help. A UNFPA report found that over 50% of teenage girls in Pakistan and India believe domestic violence can be justified for refusing sex, further illustrating deeply entrenched norms that subordinate consent to marital obedience.

Implications for Sri Lanka’s Reform Landscape

Sri Lanka, though relatively better in child marriage rates (2% by 15, 12% by 18), still mirrors regional patterns of gender–based legal exclusion – especially for married women. The Muslim Marriage and Divorce Act (MMDA) further aggravates this gap by allowing Muslim girls as young as 12 to marry, legally exempting them from statutory rape provisions under the Penal Code when forced into non–consensual sex within marriage. Unlike secular personal law registered under the general ordinance, the MMDA lacks a minimum age of consent, effectively legalizing marital rape for minors in religious marriages – a gap not present in Nepal or Bhutan legally but resembling broader regional exclusions.

Countries like Nepal and Bhutan signal possible reform trajectories: legislative elimination of exceptions, constitutional recognition of sexual autonomy, and criminal penalties for coercive sex within marriage. Sri Lanka’s path forward requires both legal overhaul (e.g., ending MMDA exception, criminalizing marital rape unconditionally) and cultural transformation, driven by grassroots advocacy and alignment with international human rights standards.

Changing the law is very important, but shifts in public awareness and social norms are equally vital to dismantle the narrative that marriage equals automatic consent. These regions require more enlightenment and more women to speak up and fight for their voice and their consent .

Fixing gaps in law is only the first step. Without addressing discriminatory practices, cultural pressures, and institutional corruption, survivors will continue to be denied dignity, safety, and justice. True reform demands a holistic approach; one that criminalizes marital rape, bans invasive medical tests, ensures timely investigations and trials, protects survivors from intimidation, and provides adequate support services. Until then, the doors to justice remain closed for too many women across South Asia.

Featured image: Credit: Vengadesh Sago on Unsplash. Infographics by Aarya Dhital, Research Consultant & Specialist on South Asia at Global Divide.