On September 5, 2025, a falling stone crushed a menstrual hut in Achham, killing thirty-five-year-old Nim Khanal and seven-year-old Kabita, and injuring Kabita’s mother. Nearly twenty years after chhaupadi was outlawed, women and girls are still forced into unsafe sheds where they risk snakebites, suffocation, sexual assault, cold — and now, a fatal landslide. The tragedy makes clear: menstrual exile remains deadly in Nepal’s western hills.

What Chhaupadi looks like, and the legal response

Chhaupadi is a Nepalese socio-religio-cultural system of menstrual seclusion: menstruating women and girls are excluded from kitchens, temples, water sources, and, frequently, forced to sleep outside the household in huts or livestock sheds.

The precise form varies: in some villages women are asked to stay in separate rooms or corners inside the home; in others, they must relocate to small, isolated mud-and-stone ‘period huts’ (chhau goths) with minimal or no ventilation, no bedding, and scant protection. Even when huts are not used, the restrictions continue in the form of bans on using the kitchen, eating certain foods (milk, yogurt, warm meals), touching other family members or animals, or accessing water. The underlying logic is that menstruating women are ‘impure’ or dangerous to the household’s spiritual and material well-being.

The practice is not limited to menstruation and is common during postpartum. The Supreme Court of Nepal declared the practice illegal in 2005, and the 2017 National Penal Code (Section 168) criminalized the forcing of women into chhaupadi, prescribing punishments of up to three months in jail or a fine of NPR 3000 or both. Yet even when huts are torn down, the social practice persists-morphed and hidden.

How widespread is Chhaupadi and how is it evolving?

In western Nepal, Chhaupadi has declined in some forms but continues to put women and girls at serious risk.

As late as 2015, surveys in Kailali and Bardiya showed that about one in five households (21%) still practiced chhaupadi, with poor housing and limited water access compounding health risks.

By 2019, the consequences were tragically clear. The National Human Rights Commission and OnlineKhabar documented at least 16 deaths in a single year linked to Chhaupadi in Sudurpaschim Province-13 in Achham and 3 in Bajura-caused by smoke inhalation, snakebites, and exposure.

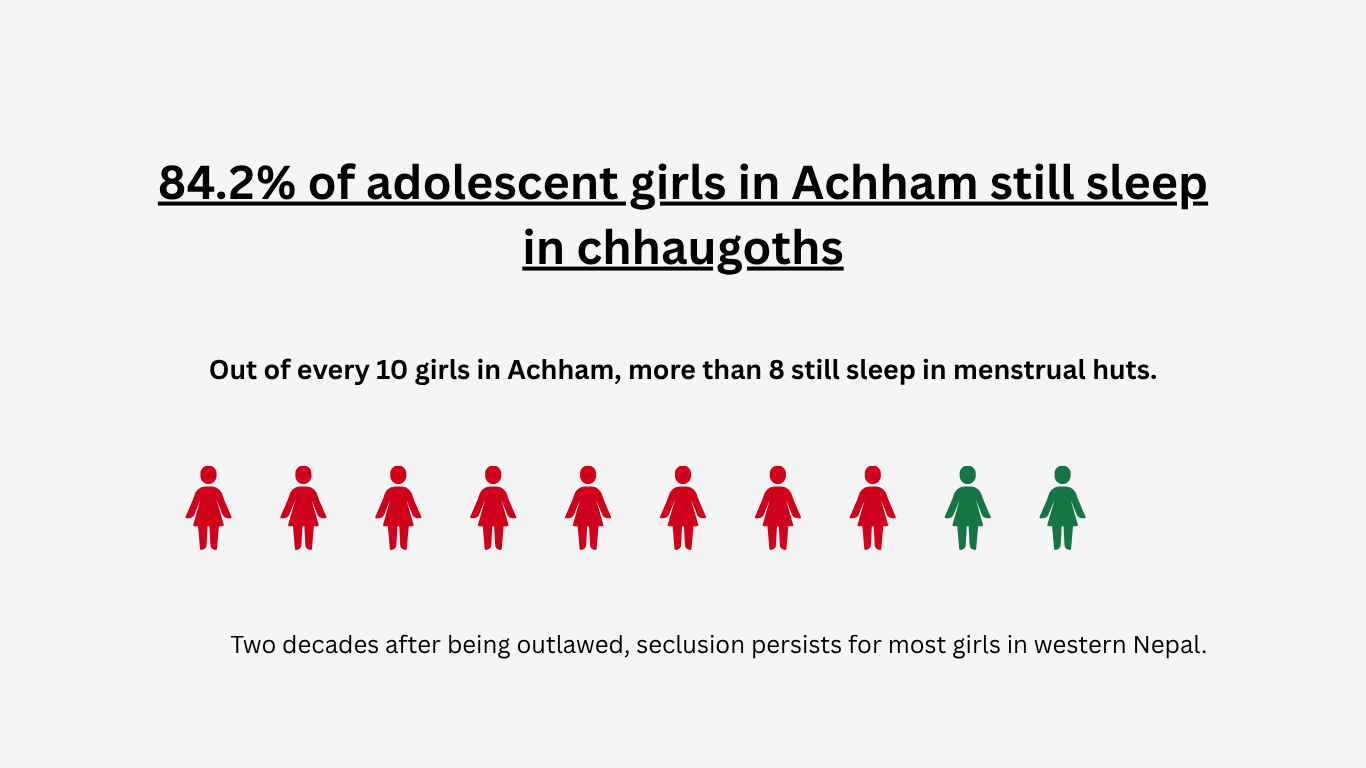

A 2021 community level-study in Mangalsen Municipality (Achham) found that the practice remained widespread: more than four out of five adolescent girls( 84.2% ) had slept in a chhaugoth during their most recent period. Disabled women and girls faced even greater risks. According to a 2022 report in The Kathmandu Post, these two vulnerable groups were more at risk of sexual violence and often lacked assistance during menstruation, making isolation especially dangerous.

Infographics by Aarya Dhital, Research Consultant & Specialist on South Asia at Global Divide.

National-level data tell a mixed story. The Nepal Demographic and Health Survey (NDHS) 2022 suggested that fewer women now report using separate huts. Yet many still face restrictions on diet, sleep, or mobility. In districts like Achham and Mangalsen, while the visible huts have declined, substitutions within or near the home are widespread-women may be confined to separate rooms, barred from the family kitchen, or forced to sleep apart from household members.

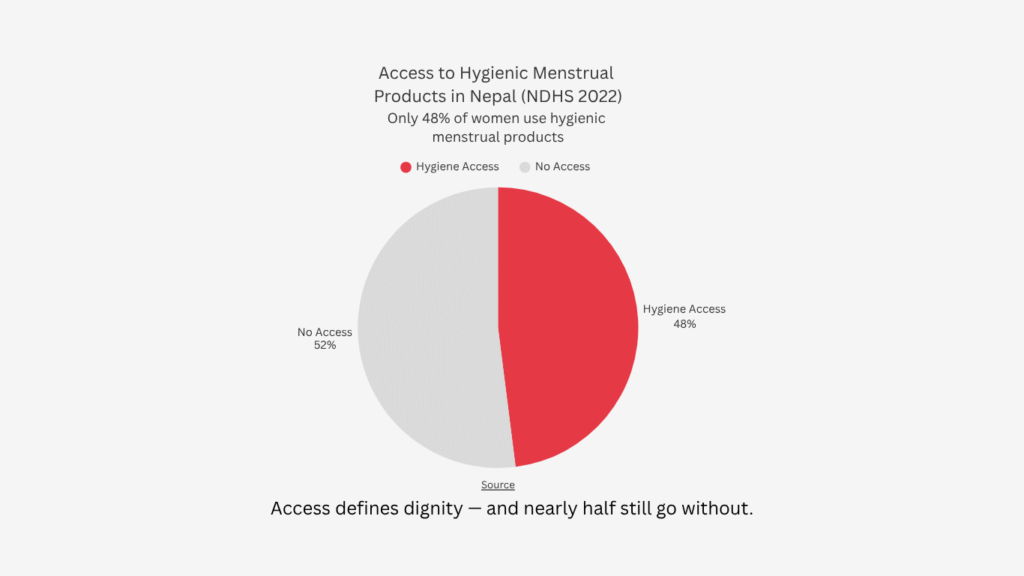

Recent cases underscore that risks persist. In 2025, a woman in Kanchanpur district died from a snakebite while sleeping in a chhaugoth. Local authorities reported that 60 huts had been demolished in one locality, only for them to be rebuilt. That same year, an analysis of NDHS-2022 revealed that fewer than half of women (48%) rely exclusively on hygienic menstrual products. Limited supplies, lack of safe disposal, and inadequate private toilets continue to fuel stigma and reinforce seclusion.

A 2025 review in Rural Development Journal concludes that despite legal bans, “Chhaupadi persists due to entrenched societal norms, limited education, and resistance to change in rural communities.” The huts may be less visible, but the underlying marginalization is far from gone.

Infographics by Aarya Dhital, Research Consultant & Specialist on South Asia at Global Divide.

Mechanisms of harm: how segregation marginalizes

Chhaupadi harms women on many fronts.

- Health and safety: Sleeping in unlined huts exposes women to cold, smoke from indoor fires, snakebites, wild animals, and sexual violence. Deaths have been recorded in the last decade from suffocation, hypothermia, snakebites, and now falling rocks.

- Hygiene: Isolation often means no private water, soap, or safe disposal. Many rely on rags or old clothes, which increase infection risk, skin irritation, and reproductive tract problems. Local studies show misconceptions about menstruation and childbirth worsen these health problems.

- Education and work: Girls miss school during seclusion; shame adds to absenteeism. Women lose workdays or wages. These interruptions deepen gender gaps in education and income.

- Civic Belonging and Dignity: When a society draws lines around who may enter kitchen, temples, or public water sources, it normalizes second-class status. Chhaupadi is not merely an episodic inconvenience-it is a cultural technology that redraws social boundaries, much like untouchability once did. Laws alone cannot undo such deeply embedded hierarchies.

- Psychological toll: Fear, shame, and isolation leave scars. Women describe loneliness and anxiety; researchers call this “social suffering” that outlasts the menstrual cycle itself. report feeling cut off from family, spiritual practice, and communal life.

Why has law alone not ended Chhaupadi?

Criminalizing enforcement of Chhaupadi was an important symbolic and legal step, but law on paper has not meant change on the ground.

- Enforcement is weak: Prosecutions and formal complaints are infrequent as many families view menstruation as a private family matter.

- Absence of an effective follow-up mechanism or procedure: Authorities tear down sheds, but families rebuild them-sometimes in riskier spots-or shift women into secret indoor exile.

- Absence of infrastructure and support: Laws do not in themselves provide private toilets, safe menstrual disposal, affordable sanitary products, or alternative housing. Without giving women practical options, the social stigma remains intact, and households may choose what seem like safer or more discreet forms of segregation rather than abandon the belief system.

- Belief runs deep: Many fear divine punishment- crop failure, livestock illness-if rules are broken. Surveys in Humla show nearly half of families still link chhaupadi to spiritual retributions.

- Poverty worsens risk: Low literacy, poverty, migration of husbands, and weak health services leave women with little support to resist family pressure. Socio-demographic studies in Mangalsen highlight that mother’s education, family type, and maternal occupation are correlated with adolescent girls’ Chhaupadi experiences.

Resistance, Reform Efforts, and Emerging Pathways

Chhaupadi’s persistence-despite criminalization and repeated condemnations-shows how deeply menstrual stigma is woven into social power and survival strategies in far-western Nepal; meaningful change therefore needs far more than laws on paper. Community-led resistance (girls’ clubs, “chhaupadi-free” villages and local activists) combined with health, school-based education and safe-house alternatives has begun to shift norms, but enforcement gaps, fear of social sanction, and political inertia keep women at risk.

International and national bodies from CEDAW’s latest observations to Human Rights Watch and Amnesty repeatedly urge a joined approach: legal accountability, funded behaviour-change programmes, and women-centered economic and educational support to replace punishment with choice. Empirical studies show that where interventions combine rights-based messaging with local leadership and livelihood options, seclusion declines-mirroring how sustained, community-rooted campaigns have eroded other harmful traditions worldwide.

Therefore, if Nepal’s reformers pair robust enforcement and follow-up mechanisms with respectful, locally driven alternatives and visible political commitment, chhaupadi can move from outlawed practice to lived irrelevance but only if policymakers, communities and international stakeholders act together to make dignity, safety and opportunity the new norm.